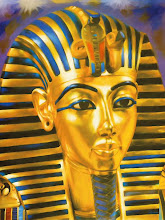

| Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus | |

|---|---|

Title page, first English-language edition, 1922 | |

| Author(s) | Ludwig Wittgenstein |

| Original title | Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung |

| Translator | Original English translation byFrank P. Ramsey and C.K. Ogden |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject(s) | Philosophy of language, logic |

| Publisher | First published in Wilhelm Ostwald's Annalen der Naturphilosophie |

| Publication date | 1921 |

| Published in English | Kegan Paul, 1922 |

| Pages | 75 |

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (Latin for "Logical-Philosophical Treatise") is the only book-length philosophical work published by the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his lifetime. It was an ambitious project: to identify the relationship between language and reality and to define the limits of science.[1] It is recognized as a significant philosophical work of the twentieth century. G. E. Moore originally suggested the work's Latin title as homage to Tractatus Theologico-Politicus by Baruch Spinoza.[2]

Wittgenstein wrote the notes for Tractatus while he was a soldier during World War I and completed it when a prisoner of war at Como and later Cassino in August 1918.[3] It was first published in German in 1921 as Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung. Tractatus was influential chiefly amongst the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle, such as Rudolf Carnap and Friedrich Waismann. Bertrand Russell's article "The Philosophy of Logical Atomism" is presented as a working out of ideas that he had learnt from Wittgenstein.[4]

Tractatus employs a notoriously austere and succinct literary style. The work contains almost no arguments as such, but, rather, consists of declarative statements which are meant to be self-evident. The statements are hierarchically numbered, with seven basic propositions at the primary level (numbered 1–7), with each sub-level being a comment on or elaboration of the statement at the next higher level (e.g., 1, 1.1, 1.11, 1.12).

Wittgenstein's later works, notably the posthumously published Philosophical Investigations, criticised many of the ideas in Tractatus.

Contents

|

Main theses

There are seven main propositions in the text. These are:

Proposition 1

The first chapter is very brief:

This along with the beginning of two can be taken to be the relevant parts of Wittgenstein's metaphysical view that he will use to support his picture theory of language. Propositions 2. & 3. These sections concern Wittgenstein's view that the sensible, changing world we perceive does not consist of substance but of facts. Proposition two begins with a discussion of objects, form and substance. This epistemic notion is further clarified by a discussion of objects or things as metaphysical substances. His use of 'composite' in 2.021 can be taken to mean a combination of form and matter, in the Platonic sense. The notion of a static unchanging Form and its identity with Substance represents the metaphysical view that has come to be held as an assumption by the vast majority of the Western philosophical tradition since Plato and Aristotle, as it was something they agreed on. “…what is called a form or a substance is not generated.” [5] (Z.8 1033b13) The opposing view states that unalterable Form, does not exist, or at least if there is such a thing, it contains an ever changing, relative substance in a constant state of flux. Although this view was held by Greeks like Heraclitus, it has existed only on the fringe of the Western tradition since then. It is commonly known now only in "Eastern" metaphysical views where the primary concept of substance is Qi, or something similar, which persists through and beyond any given Form. The former view is shown to be held by Wittgenstein in what follows... Although Wittgenstein largely disregarded Aristotle (Ray Monk's biography suggests that he never read Aristotle at all) it seems that they shared some anti-Platonist views on the universal/particular issue regarding primary substances. He attacks universals explicitly in his Blue Book. "The idea of a general concept being a common property of its particular instances connects up with other primitive, too simple, ideas of the structure of language. It is comparable to the idea that properties are ingredients of the things which have the properties; e.g. that beauty is an ingredient of all beautiful things as alcohol is of beer and wine, and that we therefore could have pure beauty, unadulterated by anything that is beautiful."[6] And Aristotle agrees... "The universal cannot be a substance in the manner in which an essence is…" [5] (Z.13 1038b17) as he begins to draw the line and drift away from the concepts of universal Forms held by his teacher Plato. The concept of Essence, taken alone is a potentiality, and its combination with matter is its actuality. “First, the substance of a thing is peculiar to it and does not belong to any other thing.” [5] (Z.13 1038b10), i.e. not universal and we know this is essence. This concept of form/substance/essence, which we've now collapsed into one, being presented as potential is also held by Wittgenstein, apparently... Here ends what Wittgenstein deems to be the relevant points of his metaphysical view and he begins in 2.1 to use said view to support his Picture Theory of Language. "The Tractatus's notion of substance is the modal analogue of Kant's temporal notion. Whereas for Kant, substance is that which “persists,” (i.e., exists at all times), for Wittgenstein it is that which, figuratively speaking, “persists” through a “space” of possible worlds." [7] Whether the Aristotelian notions of substance came to Wittgenstein via Immanuel Kant or Bertrand Russell or even arrived at intuitively, one cannot but see them. The further thesis of 2. & 3. and their subsidiary propositions is Wittgenstein’s picture theory of language. This can be summed up as follows:

Propositions 4.*-5.*

The 4s are significant as they contain some of Wittgenstein's most explicit

statements concerning the nature of philosophy and the distinction between what

can be said and what can only be shown. It is here, for instance, that he first

distinguishes between material and grammatical propositions, noting:

A philosophical treatise attempts to say something where nothing can properly be said. It is predicated upon the idea that philosophy should be pursued in a way analogous to the natural sciences; that philosophers are looking to construct true theories. This sense of philosophy does not coincide with Wittgenstein's conception of philosophy. Wittgenstein is to be credited with the invention or at least the popularization of truth tables (4.31) and truth conditions (4.431) which now constitute the standard semantic analysis of first-order sentential logic.[8][9] The philosophical significance of such a method for Wittgenstein was that it alleviated a confusion, namely the idea that logical inferences are justified by rules. If an argument form is valid, the conjunction of the premises will be logically equivalent to the conclusion and this can be clearly seen in a truth table; it is displayed. The concept of tautology is thus central to Wittgenstein's Tractarian account of logical consequence, which is strictly deductive. Proposition 6.* In the beginning of 6. Wittgenstein postulates the essential form of all sentences. He uses the notation ![[\bar p,\bar\xi, N(\bar\xi)]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/0/1/a/01a3cf5f91211db95ef402b4bd20508b.png) ,

where ,

where

The subsidiaries of 6. contain more philosophical reflections on logic, connecting to ideas of knowledge, thought, and the a priori and transcendental. The final passages argue that logic and mathematics express only tautologies and are transcendental, i.e. they lie outside of the metaphysical subject’s world. In turn, a logically "ideal" language cannot supply meaning, it can only reflect the world, and so, sentences in a logical language cannot remain meaningful if they are not merely reflections of the facts. In the final pages Wittgenstein veers towards what might be seen as religious considerations. This is founded on the gap between propositions 6.5 and 6.4. A logical positivist might accept the propositions of Tractatus before 6.4. But 6.51 and the succeeding propositions argue that ethics is also transcendental, and thus we cannot examine it with language, as it is a form of aesthetics and cannot be expressed. He begins talking of the will, life after death, and God. In his examination of these issues he argues that all discussion of them is a misuse of logic. Specifically, since logical language can only reflect the world, any discussion of the mystical, that which lies outside of the metaphysical subject's world, is meaningless. This suggests that many of the traditional domains of philosophy, e.g. ethics and metaphysics, cannot in fact be discussed meaningfully. Any attempt to discuss them immediately loses all sense. This also suggests that his own project of trying to explain language is impossible for exactly these reasons. He suggests that the project of philosophy must ultimately be abandoned for those logical practices which attempt to reflect the world, not what is outside of it. The natural sciences are just such a practice, he suggests. At the very end of the text he borrows an analogy from Arthur Schopenhauer, and compares the book to a ladder that must be thrown away after one has climbed it. Proposition 7 As the last line in the book, proposition 7 has no supplementary propositions. It ends the book with a rather elegant and stirring proposition: "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." („Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen.“) Both the first and the final proposition have acquired something of a proverbial quality in German, employed as aphorisms independently of discussion of Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein's conclusion in Proposition 7 echoes the Old Testament words of Jesus ben Sirach (ישוע בן סירא, Yešwaʿ ven Siraʾ): What is too sublime for you, do not seek; do not reach into things that are hidden from you. What is committed to you, pay heed to; what is hidden is not your concern. (Sirach 3: 21-22). Saint Thomas Aquinas addressed ben Sirach--and, by extension, Wittgenstein--in the First Article, First Part, of his Summa Theologica: Following Aquinas, moral philosophers and theologians have addressed the problem of religious language for centuries. Moreover, there has been extensive commentary on the relationship between the respective treatises of Wittgenstein (Tractatus) and Aquinas (Summa Theologica).[11][12] In addition, Fergus Gordon Kerr, a Roman Catholic priest of the Order of Preachers founded by Saint Dominic, notes that "theological questions lie between the lines of all of Wittgenstein's writing. It is hard to think of a great philosopher, at least since Nietzsche, whose work is equally pervaded by theological considerations."[13] The Picture Theory A prominent view set out in the Tractatus is the picture theory. The picture theory is a proposed description of the relation of representation.[14] This view is sometimes called the picture theory of language, but Wittgenstein discusses various representational picturing relationships, including non-linguistic "pictures" such as photographs and sculptures (TLP 2.1–2.225).[14] According to the theory, propositions can "picture" the world, and thus accurately represent it.[14] If someone thinks the proposition, "There is a tree in the yard," then that proposition accurately pictures the world if and only if there is a tree in the yard.[15] If there is no tree in the yard, the proposition does not accurately picture the world. Although something need not be a proposition to represent something in the world, Wittgenstein was largely concerned with the way propositions function as representations.[14] Wittgenstein was inspired for this theory by the way that traffic courts in Paris reenact automobile accidents.[16] A toy car is a representation of a real car, a toy truck is a representation of a real truck, and dolls are representations of people. In order to convey to a judge what happened in an automobile accident, someone in the courtroom might place the toy cars in a position like the position the real cars were in, and move them in the ways that the real cars moved. In this way, the elements of the picture (the toy cars) are in spatial relation to one another, and this relation itself pictures the spatial relation between the real cars in the automobile accident.[17] When writing about these picturing situations, Wittgenstein used the word "Bild," which may be translated as "picture" or "model". Although the theory is commonly known as the "picture" theory, "model" is probably a more appropriate way of thinking of what Wittgenstein meant by "Bild."[16] Pictures have what Wittgenstein calls Form der Abbildung, or pictorial form, in virtue of their being similar to what they picture. The fact that the toy car has four wheels, for example, is part of its pictorial form, because the real car had four wheels. The fact that the toy car is significantly smaller than the real car is part of its representational form, or the differences between the picture and what it pictures, which Wittgenstein is interpreted to mean by Form der Darstellung.[18] This picturing relationship, Wittgenstein believed, was our key to understanding the relationship a proposition holds to the world.[14] We can't see a proposition like we can a toy car, yet he believed a proposition must still have a pictorial form.[19] The pictorial form of a proposition is best captured in the pictorial form of a thought, as thoughts consist only of pictorial form. This pictorial form is logical structure.[20] Wittgenstein believed that the parts of the logical structure of thought must somehow correspond to words as parts of the logical structure of propositions, although he did not know exactly how.[21] Here, Wittgenstein ran into a problem he acknowledged widely: we cannot think about a picture outside of its representational form.[20] Recall that part of the representational form of toy cars is their size—specifically, the fact that they are necessarily smaller than the actual cars.[18] Just so, a picture cannot express its own pictorial form.[20] One outcome of the picture theory is that a priori truth does not exist. Truth comes from the accurate representation of a state of affairs (i.e., some aspect of the real world) by a picture (i.e., a proposition). "The totality of true thoughts is a picture of the world (TLP 3.01)." Thus without holding a proposition up against the real world, we cannot tell whether the proposition is true or false.[20] Logical Atomism Although Wittgenstein did not use the term himself, his metaphysical view throughout the Tractatus is commonly referred to as logical atomism. While his logical atomism resembles that of Bertrand Russell, the two views are not strictly the same.[22] Russell's theory of descriptions is a way of logically analyzing objects in a meaningful way regardless of that object's existence. According to the theory, a statement like "There is a man to my left" is made meaningful by analyzing it into: "There is some x such that x is a man and x is to my left, and for any y, if y is a man and y is to my left, y is identical to x". If the statement is true, x refers to the man to my left.[23] Whereas Russell believed the names (like x) in his theory should refer to things we can know epistemically, Wittgenstein thought they should refer to the "objects" that make up his metaphysics.[24] By objects, Wittgenstein did not mean physical objects in the world, but the absolute base of logical analysis, that can be combined but not divided (TLP 2.02–2.0201).[22] According to Wittgenstein's logical-atomistic metaphysical system, objects each have a "nature," which is their capacity to combine with other objects. When combined, objects form "states of affairs." A state of affairs that obtains is a "fact." Facts make up the entirety of the world. Facts are logically independent of one another, as are states of affairs. That is, one state of affair's (or fact's) existence does not allow us to infer whether another state of affairs (or fact) exists or does not exist.[25] Within states of affairs, objects are in particular relations to one another.[26] This is analogous to the spatial relations between toy cars discussed above. The structure of states of affairs comes from the arrangement of their constituent objects (TLP 2.032), and such arrangement is essential to their intelligibility, just as the toy cars must be arranged in a certain way in order to picture the automobile accident.[26] A fact might be thought of as the obtaining state of affairs that Madison is in Wisconsin, and a possible (but not obtaining) state of affairs might be Madison's being in Utah. These states of affairs are made up of certain arrangements of objects (TLP 2.023). However, Wittgenstein does not specify what objects are. Madison, Wisconsin, and Utah cannot be atomic objects: they are themselves composed of numerous facts.[26] Instead, Wittgenstein believed objects to be the things in the world that would correlate to the smallest parts of a logically analyzed language, such as names like x. Our language is not sufficiently (i.e., not completely) analyzed for such a correlation, so one cannot say what an object is.[27] We can, however, talk about them as "indestructible" and "common to all possible worlds."[26] Wittgenstein believed that the philosopher's job was to discover the structure of language through analysis.[28] Anthony Kenny provides a useful analogy for understanding Wittgenstein's logical atomism: a slightly modified game of chess.[29] Just like objects in states of affairs, the chess pieces do not alone constitute the game—their arrangements, together with the pieces (objects) themselves, determine the state of affairs.[27] Through Kenny's chess analogy, we can see the relationship between Wittgenstein's logical atomism and his picture theory of representation.[30] For the sake of this analogy, the chess pieces are objects, they and their positions constitute states of affairs and therefore facts, and the totality of facts is the entire particular game of chess.[27] We can communicate such a game of chess in the exact way that Wittgenstein says a proposition represents the world.[30] We might say "WR/KR1" to communicate a white rook's being on the square commonly labeled as king's rook 1. Or, to be more thorough, we might make such a report for every piece's position.[30] The logical form of our reports must be the same logical form of the chess pieces and their arrangement on the board in order to be meaningful. Our communication about the chess game must have as many possibilities for constituents and their arrangement as the game itself.[30] Kenny points out that such logical form need not strictly resemble the chess game. The logical form can be had by the bouncing of a ball (for example, twenty bounces might communicate a white rook's being on the king's rook 1 square). One can bounce a ball as many times as one wishes, which means the ball's bouncing has "logical multiplicity," and can therefore share the logical form of the game.[31] A motionless ball cannot communicate this same information, as it does not have logical multiplicity.[30] The Saying/Showing Distinction According to the picture theory, when a proposition is thought or expressed, each of its constituent parts correspond (if the proposition is true) to some aspect of the world. However, the correspondence itself is something Wittgenstein believed we could not say anything about. We can say that there is correspondence, but the correspondence itself can only be shown.[32] His logical-atomistic metaphysical view led Wittgenstein to believe that we could not say anything about the relationship that pictures bear to what they picture. Thus the picture theory allows us to be shown that some things can be said while others are shown.[33] Our language is not sufficient for expressing its own logical structure.[34] Wittgenstein believed that the philosopher's job was to discover the structure of language through analysis.[28] Something sayable must have content that is fully intelligible to a person without that person's knowing if it is true or false.[15] In the case of something's inability to be said, such as the logical structure of language, it can only be shown.[20] A proposition can say something, such as "George is tall," but it cannot express (say) this function of itself. It can only show that it says that George is tall.[15] Reception and influence Wittgenstein concluded that with the Tractatus he had resolved all philosophical problems. Meanwhile, the book was translated into English by C. K. Ogden with help from the Cambridge mathematician and philosopher Frank P. Ramsey, then still in his teens. Ramsey later visited Wittgenstein in Austria. Translation issues make the concepts hard to pinpoint, especially given Wittgenstein's usage of terms and difficulty in translating ideas into words.[35] The Tractatus caught the attention of the philosophers of the Vienna Circle (1921–1933), especially Rudolf Carnap and Moritz Schlick. The group spent many months working through the text out loud, line by line. Schlick eventually convinced Wittgenstein to meet with members of the circle to discuss the Tractatus when he returned to Vienna (he was then working as an architect). Although the Vienna Circle's logical positivists appreciated the Tractatus, they argued that the last few passages, including Proposition 7, are confused. Carnap hailed the book as containing important insights, but encouraged people to ignore the concluding sentences. Wittgenstein responded to Schlick, commenting, "...I cannot imagine that Carnap should have so completely misunderstood the last sentences of the book and hence the fundamental conception of the entire book."[36] A more recent interpretation comes from the New Wittgenstein family of interpretations (2000-).[37] This so-called "resolute reading" is controversial and much debated.[citation needed] The main contention of such readings is that Wittgenstein in the Tractatus does not provide a theoretical account of language that relegates ethics and philosophy to a mystical realm of the unsayable. Rather, the book has a therapeutic aim. By working through the propositions of the book the reader comes to realize that language is perfectly suited to all his needs, and that philosophy rests on a confused relation to the logic of our language. The confusion that the Tractatus seeks to dispel is not a confused theory, such that a correct theory would be a proper way to clear the confusion, rather the need of any such theory is confused. The method of the Tractatus is to make the reader aware of the logic of our language as he is already familiar with it, and the effect of thereby dispelling the need for a theoretical account of the logic of our language spreads to all other areas of philosophy. Thereby the confusion involved in putting forward e.g. ethical and metaphysical theories is cleared in the same coup. Wittgenstein would not meet the Vienna Circle proper, but only a few of its members, including Schlick, Carnap, and Waissman. Often, though, he refused to discuss philosophy, and would insist on giving the meetings over to reciting the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore with his chair turned to the wall. He largely broke off formal relations even with these members of the circle after coming to believe Carnap had used some of his ideas without permission.[38] The Tractatus was the theme of a 1992 film by the Hungarian filmmaker Peter Forgacs. The 32-minute production, named Wittgenstein Tractatus, features citations from the Tractatus and other works by Wittgenstein. Editions Tractatus is the English translation of

Notes

References

External links

English versions online

Wikipedia Article Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tractatus_Logico-Philosophicus

|

stands for all atomic propositions,

stands for all atomic propositions, stands for any subset of propositions, and

stands for any subset of propositions, and stands for the negation of all propositions making up

stands for the negation of all propositions making up

.jpg)

.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

.jpg)