Gnosticism includes a variety of religious movements, mostly Christian in nature, in the ancient Hellenistic society around the Mediterranean. Although origins are disputed, the period of activity for most of these movements flourished from approximately the time of the founding of Christianity until the 4th century when the writings and activities of groups deemed heretical or pagan were actively suppressed. The only information available on these movements for many centuries was the characterizations of those writing against them, and the few quotations preserved in such works.

The late 19th century saw the publication of popular sympathetic studies making use of recently rediscovered source materials. In this period there was also revival of the Gnostic religious movement in France. The emergence of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945, greatly increased the amount of source material available. Its translation into English and other modern languages in 1977, resulted in a wide dissemination, and has as a result had observable influence on several modern figures, and upon modern Western culture in general. This article attempts to summarize those modern figures and movements that have been influenced by Gnosticism, both prior and subsequent to the Nag Hammadi discovery.

Contents

1 Late 19th century

1.1 Charles William King

1.2 Madame Blavatsky

1.3 G. R. S. Mead

1.4 The Gnostic Church revival in France

2 Early to mid-20th century

2.1 Carl Jung

2.1.1 The Jung Codex

2.2 French Gnostic Church split, reintegration, and continuation

2.3 Modern sex magic associated with Gnosticism

2.3.1 Modern sex magic brought to South America

2.4 The Gnostic Society

3 Mid-20th century

3.1 Ecclesia Gnostica

3.1.1 Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum

3.2 Samael Aun Weor and sex magic in South America

3.3 Hans Jonas

3.4 Eric Voegelin's anti-modernist 'gnostic thesis'

4 The Nag Hammadi Library

5 Gnosticism in popular culture

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Late 19th century

Source materials were discovered in the 18th century. In 1769 the Bruce Codex was brought to England from Upper Egypt by the famous Scottish traveller Bruce, and subsequently bequeathed to the care of the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Sometime prior to 1785 The Askew Codex (aka Pistis Sophia) was bought by the British Museum from the heirs of Dr. Askew. Pistis Sophia text and Latin translation of the Askew Codex by M. G. Schwartze published in 1851. Although discovered in 1896 the Coptic Berlin Codex (aka. the Akhmim Codex), is not 'rediscovered' until the 20th century.

Charles William King

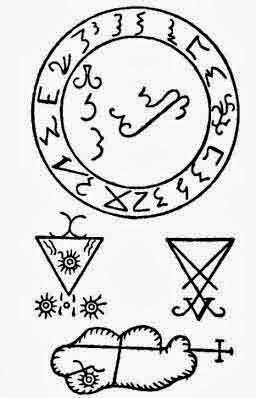

Charles William King was a British writer and collector of ancient gemstones with magical inscriptions. His collection was sold because of his failing eyesight, and was presented in 1881 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. King was recognized as one of the greatest authorities on gems.[1]

In The Gnostics and their Remains (1864, 1887 2nd ed.) King sets out to show that rather than being a Western heresy, the origins of Gnosticism are to be found in the East, specifically in Buddhism. This theory was embraced by Blavatsky, who argued that it was plausible, but rejected by GRS Mead. According to Mead, King's work "lacks the thoroughness of the specialist."[2]

Madame Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, co-founder of the Theosophical Society, wrote extensively on Gnostic ideas. A compilation of her writings on Gnosticism is over 270 pages long.[3] The first edition of King's The Gnostics and Their Remains was repeatedly cited as a source and quoted in Isis Unveiled.

G. R. S. Mead

G. R. S. Mead became a member of Blavatsky's Theosophical Society in 1884. He left the teaching profession in 1889 to become Blavatsky's private secretary, which he was until her death in 1891. Mead's interest in Gnosticism was likely awakened by Blavatsky who discussed it at length in Isis Unveiled.[4]

In 1890-1 Mead published a serial article on Pistis Sophia in Lucifer magazine, the first English translation of that work. In an article in 1891, Mead argues for the recovery of the literature and thought of the West at a time when Theosophy was largely directed to the East. Saying that this recovery of Western antique traditions is a work of interpretation and "the rendering of tardy justice to pagans and heretics, the reviled and rejected pioneers of progress..."[5] This was the direction his own work was to take.

The first edition of his translation of Pistis Sophia appeared in 1896. From 1896-8 Mead published another serial article in the same periodical, "Among the Gnostics of the First Two Centuries," that laid the foundation for his monumental compendium Fragments of a Faith Forgotten in 1900. Mead serially published translations from the Corpus Hermeticum from 1900-05. The next year he published Thrice-Greatest Hermes a massive comprehensive three volume treatise. His series Echoes of the Gnosis was published in 12 booklets in 1908. By the time he left the Theosophical Society in 1909, he had published many influential translations, commentaries, and studies of ancient Gnostic texts. "Mead made Gnosticism accessible to the intelligent public outside of academia..."[6] Mead's work has had and continues to have widespread influence.[7]

The Gnostic Church revival in France

After a series of visions and archival finds of Cathar-related documents, a librarian named Jules-Benoît Stanislas Doinel du Val-Michel (aka Jules Doinel) establishes the Eglise Gnostique (French: Gnostic Church). Founded on extant Cathar documents with the Gospel of John and strong influence of Simonian and Valentinian cosmology, the church was officially established in the autumn of 1890 in Paris, France. Doinel declared it "the era of Gnosis restored." Liturgical services were based on Cathar rituals. Clergy was both male and female, having male bishops and female "sophias."[8][9]

Doinel resigned and converted to Roman Catholicism in 1895, one of many duped by Léo Taxil's anti-masonic hoax, writing Lucifer Unmasked a book attacking freemasonry. Taxil unveiled the hoax in 1897. Doinel was readmitted to the Gnostic church as a bishop in 1900.

Early to mid-20th century

Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung evinced a special interest in Gnosticism from at least 1912, when he wrote enthusiastically about the topic in a letter to Freud. After what he called his own 'encounter with the unconscious,' Jung sought for external evidence of this kind of experience. He found such evidence in Gnosticism, and also in Alchemy, which he saw as a continuation of Gnostic thought, and of which more source material was available.[10] In his study of the Gnostics, Jung made extensive use of the work of GRS Mead. Jung visited Mead in London to thank him for the Pistis Sophia, the two corresponded, and Mead visited Jung in Zürich.[11]

Jung saw the Gnostics not as syncretic schools of mixed theological doctrines, but as genuine visionaries, and saw their imagery not as myths but as records of inner experience.[12] He wrote that "The explanation of Gnostic ideas 'in terms of themselves,' i.e., in terms of their historical foundations, is futile, for in that way they are reduced only to their less developed forestages but not understood in their actual significance."[13] Instead, he worked to understand and explain Gnosticism from a psychological standpoint. (See Jungian interpretation of religion.) While providing something of an ancient mirror of his work, Jung saw "his psychology not as a contemporary version of Gnosticism, but as a contemporary counterpart to it."[14]

Jung reported a series of experiences in the winter of 1916-17 that inspired him to write Septem Sermones ad Mortuos (Latin: Seven Sermons to the Dead).[15][16]

The Jung Codex

Through the efforts of Gilles Quispel, the Jung Codex was the first codex brought to light from the Nag Hammadi Library. It was purchased by the Jung Institute and ceremonially presented to Jung in 1953 because of his great interest in the ancient Gnostics.[17] First publication of translations of Nag Hammadi texts in 1955 with the Jung Codex by H. Puech, Gilles Quispel, and W. Van Unnik.

French Gnostic Church split, reintegration, and continuation

Jean Bricaud had been involved with the Eliate Church of Carmel of Eugene Vintras, the remnants of Fabré-Palaprat's l'Église Johannites des Chretiens Primitif (Johannite Church of the Primitive Christians), and the Martinist Order before being consecrated a bishop of l'Église Gnostique in 1901. In 1907 Bricaud established a church body that combined all of these, becoming patriarch under the name Tau Jean II. The impetus for this was to use the Western Rite. Briefly called the Eglise Catholique Gnostique (Gnostic Catholic Church), the name was changed to Eglise Gnostique Universelle (Universal Gnostic Church, EGU) in 1908. The close ties between the church and Martinism were formalized in 1911. Bricaud received consecration in the Villate line of Apostolic Succession in 1919.[8][9]

The original church body founded by Doinel continued under the name Eglise Gnostique du France (Gnostic Church of France) until it was disbanded in favor of the EGU in 1926. The EGU continued until 1960 when it was disbanded by Robert Amberlain (Tau Jean III) in favor of Eglise Gnostique Apostolique that he had founded in 1958.[18] It is active in France (including Martinique), the Ivory Coast, and the Midwestern United States.

Modern sex magic associated with Gnosticism

The use of the term 'gnostic' by sexual magic groups is a modern phenomenon. Hugh Urban concludes that, "despite the very common use of sexual symbolism throughout Gnostic texts, there is little evidence (apart from the accusations of the early church) that the Gnostics engaged in any actual performance of sexual rituals, and certainly not anything resembling modern sexual magic."[19] Modern sexual magic began with Paschal Beverly Randolph.[20] The connection to Gnosticism came by way of the French Gnostic Church with its close ties to the strong esoteric current in France, being part of the same highly interconnected milieu of esoteric societies and orders from which the most influential of sexual magic orders arose, the Ordo Templi Orientis (Order of Oriental Templars, OTO).

Theodor Reuss founded the OTO as an umbrella occult organization with sexual magic at its core.[21] After Reuss came into contact with French Gnostic Church leaders at a Masonic and Spiritualist conference in 1908, he founded Die Gnostische Katholische Kirche (the Gnostic Catholic Church), under the auspices of the OTO.[8] Reuss subsequently dedicated the OTO to the promulgation of Crowley's philosophy of Thelema. It is for this church body, called in Latin the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (EGC), that Aleister Crowley wrote the Ecclesiæ Gnosticæ Catholicæ Canon Missæ ("Canon of the Mass of the Gnostic Catholic Church"),[22] the central ritual of the OTO that is now commonly called the Gnostic Mass.

Modern sex magic brought to South America

Arnoldo Krumm-Heller traveled in occult circles at the turn of the century where he studied with notable figures such as Gérard Encausse of the Martinist Order and Franz Hartmann of the OTO. In 1910 he founded the Iglesia Gnostica (Gnostic Church) in Mexico. Not finding as much success as he hoped for, he moved through Latin America before settling in Brazil. There he founded the Fraternidad de Rosacruz Antiqua (Fraternity of the Ancient Rosicrucians), following Randolph's usage. Krumm-Heller moved back to Germany in 1920, where he made contact with Aleister Crowley. Krumm-Heller kept a low profile through World War II, but when he was able to travel again after the war, he resumed contact with his Latin America students. Between that time and his death in 1949, Krumm-Heller encountered and subsequently mentored Victor Rodriguez who would subsequently take the name Samael Aun Weor.[23] Weor states that Krumm-Heller taught a form of Sexual Magic without ejaculation that would become the core of his own teachings.

The Gnostic Society

The Gnostic Society, was founded for the study of gnosticism in 1928 and incorporated in 1939 by Theosophists James Morgan Pryse and his brother John Pryse in Los Angeles.[24][25] Since 1963 it has been under the direction of Stephan Hoeller and operates in association with the Ecclesia Gnostica. Initially begun as an archive for a usenet newsgroup circa 1993, the Gnosis Archive expanded beyond that purpose. It was the first web site to offer historic and source materials on Gnosticism, and continues to do so.

Mid-20th century

Ecclesia Gnostica

Established in 1953 by the Most Rev. Richard Duc de Palatine in England under the name 'the Pre-nicene Gnostic Catholic Church', the Ecclesia Gnostica (Latin: "Church of Gnosis" or "Gnostic Church") is said to represent 'the English Gnostic tradition', although it has ties to, and has been influenced by, the French Gnostic church tradition. It is affiliated with the Gnostic Society, an organization dedicated to the study of Gnosticism. The presiding bishop is the Rt. Rev. Stephan A. Hoeller, who has written extensively on Gnosticism.[15][24]

Centered in Los Angeles, the Ecclesia Gnostica has parishes and educational programs of the Gnostic Society spanning the Western US and also in the Kingdom of Norway.[24][25] The lectionary and liturgical calendar of the Ecclesia Gnostica have been widely adopted by subsequent Gnostic churches, as have the liturgical services in use by the church, though in somewhat modified forms.

Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum

The Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum (EGM), commonly known as "the Church of Gnosis" or "the Gnostic Sanctuary," was initially established in Palo Alto by bishop Rosamonde Miller as a parish of the Ecclesia Gnostica, but soon became an independent body with emphasis on the divine feminine. The Gnostic Sanctuary is now located in Mountain View, California. [24][25] The EGM also claims a distinct lineage of Mary Magdalene from a surviving tradition in France.[26]

Samael Aun Weor and sex magic in South America

Victor Rodriguez left the FRA after the death of Krumm Heller. He reports an experience of being called to his new mission by the venerable white lodge (associated with Theosophy). Weor taught a "New Gnosis," consisting of Sexual Magic without ejaculation he called the Arcanum AZF. For him it is "the synthesis of all religions, schools and sects." Moving through Latin America, he finally settled in Mexico where he founded the Movimiento Gnostico Cristiano Universal (MGCU) (Universal Gnostic Christian Movement), then subsequently founded the Iglesia Gnostica Cristiana Universal (Universal Gnostic Christian Church) and the Associacion Gnostica de Estudios Antropologicos Culturales y Cientificos (AGEAC) (Gnostic Association of Scientific, Cultural and Anthropological Studies) to spread his teachings.[27]

The MGCU became defunct by the time of Weor's death in December 1977. However, his disciples subsequently formed new organizations to spread Weor's teachings, under the umbrella term 'the International Gnostic Movement'. These organizations are currently very active via the Internet and have centers established in Latin America, the US, Australia, and Europe.[28]

Hans Jonas

The philosopher Hans Jonas wrote extensively on Gnosticism, interpreting it from an existentialist viewpoint. For some time, his study The Gnostic Religion: The message of the alien God and the beginnings of Christianity published in 1958, was widely held to be a pivotal work, and it is as a result of his efforts that the Syrian-Egyptian/Persian division of Gnosticism came to be widely used within the field. The second edition, published in 1963, included the essay “Gnosticism, Existentialism, and Nihilism.”

Eric Voegelin's anti-modernist 'gnostic thesis'

In the 1950s, Eric Voegelin entered into an academic debate concerning the classification of modernity following Karl Löwith's 1949 Meaning in History: the Theological Implications of the Philosophy of History; and Jacob Taubes's 1947 Abendländishe Eschatologie. In this context, Voegelin put forward his "gnosticism thesis": criticizing modernity by identifying an "immanentist eschatology" as the "gnostic nature" of modernity. Differing with Löwith, he did not criticize eschatology as such, but rather the immanentization which he described as a "pneumopathological" deformation. Voegelin's gnosticism thesis became popular in neo-conservative and cold war political thought.[29]

The Nag Hammadi Library

Main article: Nag Hammadi Library

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nag_Hammadi_Library

Gnosticism in popular culture

Main article: Gnosticism in popular culture

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnosticism_in_popular_culture

Gnosticism has seen something of a resurgence in popular culture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. This may be related, certainly, to the sudden availability of Gnostic texts to the reading public, following the emergence of the Nag Hammadi library.

See also

Gnostic Association of Anthropological, Cultural and Scientific Studies

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnostic_Association_of_Anthropological,_Cultural_and_Scientific_Studies

teaching the doctrine of Samael Aun Weor

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samael_Aun_Weor

Gnostic church

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnostic_church

Gnostic saint

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnostic_saint

Notes

1.^ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

2.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 8-9

3.^ Hoeller (2002) p. 167

4.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 8

5.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 56-7

6.^ Hoeller (2002) p. 170

7.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 31-2

8.^ a b c Pearson, J. (2007) p. 47

9.^ a b Hoeller (2002) p. 176-8

10.^ Segal (1995) p. 26

11.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 1, 30-1

12.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 30

13.^ Jung (1977) p. 652

14.^ Segal (1995) p. 30

15.^ a b Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 31

16.^ Hoeller (1989) p. 7

17.^ Jung (1977) p. 671

18.^ Pearson, J. (2007) p. 131

19.^ Urban (2006) p. 36 note 68

20.^ Urban (2006) p. 36

21.^ Greer (2003) p. 221-2

22.^ The Equinox III:1 (1929) p. 247

23.^ Dawson (2007) p. 55-57

24.^ a b c d Pearson, B. (2007) p. 240

25.^ a b c Smith (1995) p. 206

26.^ Keizer, Lewis (2000). The Wandering Bishops: Apostles of a New Spirituality. St. Thomas Press. pp. 48. http://www.hometemple.org/WanBishWeb%20Complete.pdf.

27.^ Dawson (2007) p. 54-60

28.^ Dawson (2007) p. 60-65

29.^ Weiss (2000)

References

Crowley, Aleister (2007). The Equinox vol. III no. 1. San Francisco: Weiser. ISBN 9781578633531.

Dawson, Andrew (2007). New era, new religions: religious transformation in contemporary Brazil. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754654339.

Goodrick-Clarke, Clare (2005). G. R. S. Mead and the Gnostic Quest. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 155643572x.

Greer, John Micheal (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. St. Paul: Llewellyn. ISBN 1567183360.

Hoeller, Stephan (1989). The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead. Quest Books. ISBN 083560568X.

Hoeller, Stephan. Gnosticism: New light on the ancient tradition of inner knowing. Quest Books.

Jung, Carl Gustav (1977). The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, NJ: Bollingen (Princeton University). ISBN 0710082916.

Mead, GRS (1906 (2nd ed.)). Fragments of a Faith Forgotten. Theosophical Society.

Pearson, Birger (2007). Ancient Gnosticism: Traditions and Literature. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800632588.

Pearson, Joanne (2007). Wicca and the Christian Heritage. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415254140.

Segal, Robert (1995). "Jung's Fascination with Gnosticism". In Segal, Robert. The Allure of Gnosticism: the Gnostic experience in Jungian psychology and contemporary culture. Open Court. pp. 26–38. ISBN 0812692780.

Smith, Richard (1995). "The revival of ancient Gnosis". In Segal, Robert. The Allure of Gnosticism: the Gnostic experience in Jungian psychology and contemporary culture. Open Court. pp. 206. ISBN 0812692780.

Urban, Hugh B. (2006). Magia Sexualis: Sex, Magic, and Liberation in modern Western esotericism. University of California. ISBN 0520247760.

Weiss, Gilbert (2000). "Between gnosis and anamnesis--European perspectives on Eric Voegelin". The Review of Politics 62 (4): 753–776. doi:10.1017/S003467050004273X. 65964268.

Wasserstrom, Steven M. (1999). Religion after religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. ISBN 0691005400.

External links

"The Gnostics and their Remains" - online text of the book

http://www.sacred-texts.com/gno/gar/

Extensive on-line collection of the writings of GRS Mead (at the Gnosis Archive)

http://www.gnosis.org/library/grs-mead/mead_index.htm

The Gnostic Society Library

http://www.gnosis.org/library.html

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnosticism_in_modern_times

__________________

Info On Voices of Gnosticism:

http://www.occultofpersonality.net/miguel-conner-and-voices-of-gnosticism/

terça-feira, 27 de dezembro de 2011

sábado, 24 de dezembro de 2011

Maçonaria e Magia (The Magical Mason)

About the Author:

William Wynn Westcott (17 December 1848 – 30 July 1925) was a coroner, ceremonial magician, and Freemason born in Leamington, Warwickshire, England.[1] He was a Supreme Magus (chief) of the S.R.I.A and went on to co found the Golden Dawn.

Extract Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wynn_Westcott

More Info & Related: http://www.amazon.com/Magical-Mason-Forgotten-Hermetic-Physician/dp/0850303737/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1324748236&sr=1-1 , http://www.allbookstores.com/R-A-Gilbert/author ; http://www.librarything.com/author/gilbertra & http://pt.scribd.com/doc/24111099/R-A-Gilbert-The-Magical-Mason

Marcadores:

books,

editora pensamento,

golden dawn,

masonry,

qabalah,

R. A. Gilbert,

rosicrucianism,

William Wynn Westcott_

segunda-feira, 19 de dezembro de 2011

A Franco-Maçonaria (Ibrasa)

About The Author (in French):

Robert Ambelain (Paris, 2 septembre 1907 – Paris, 27 mai 1997) est un auteur français, spécialisé dans l'ésotérisme, l'occultisme et l'astrologie. Homme de lettres, historien et membre sociétaire des Gens de Lettres et de l'Association des écrivains de langue française « mer outre-mer », il est l'auteur de 42 ouvrages (dont certains sous le pseudonyme d'Aurifer).

Biographie

Son intérêt pour l'ésotérisme commença par l'astrologie, vers 1921. Entre 1937 et 1942 il a publié un Traité d'astrologie ésotérique en trois volumes. En 1946, il a été consacré évêque dans l'Église gnostique universelle sous le nom de Tau Robert. Fondateur de l'Église gnostique apostolique, il a été patriarche de l'Église gnostique universelle en 1960 sous le nom de Tau Jean III[1]

Franc-maçon, il fut Grand Maître mondial de la Grande loge de Memphis-Misraïm et fondateur d'une association d'occultisme et martiniste[2].

Il a écrit notamment Le Dragon d'or, Le Cristal magique, La Magie sacrée et Jésus ou le mortel secret des Templiers (Robert Laffont, « Les énigmes de l'univers », 1970). Il décède en 1997 à l'âge de 90 ans.

Extract Source: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Ambelain

sábado, 19 de novembro de 2011

Segredos da Simbologia - Sociedades Secretas Medievais

Documentary YouTube Trailer:

More Info:

http://www.amazon.com/Keys-Code-Unlocking-Secrets-Symbols/dp/B0014JLMEE

Marcadores:

documentaries,

dvds,

filmes unimundos II,

Philip Gardiner_,

symbology,

Tim Wallace-Murphy

O Código Da Vinci (Edição Especial)

O Código Da Vinci - Verdade ou Mentira?

( http://www.amazon.com/Exposing-Davinci-Code-Paul-Sharrett/dp/B000ALM42G )

O Código Da Vinci - Mistério ou Conspiração?

( http://www.amazon.com/Unlocking-DaVincis-Code-Mystery-Conspiracy/dp/B0002F6BA6 )

Marcadores:

conspiracies,

da vinci code,

documentaries,

dvds,

filmes unimundos II,

grail mysteries,

historical enigmas

quinta-feira, 3 de novembro de 2011

O Código Da Vinci Descodificado (Cracking the Da Vinci Code)

About The Author:

Simon Cox (December 11, 1966 -) is a British author who is the ex editor-in-chief of Into The DUAT magazine and previously also of "Phenomena" magazine in the US, he was the founder of Henu Productions. Cox is an alternative historian who researches the occult, conspiracy theory, secret societies, etc.

His first Book, Cracking The Da Vinci Code, was a worldwide bestseller and chart topper in several international markets.

In 2005, his book, Illuminating Angels & Demons, was featured in a documentary of the same name[1] released by Allumination FilmWorks[2][3] which featured Jim Marrs and others as contributing authors.

In 2006, Cox appeared in the documentary Richard Hammond and the Holy Grail.[4]

In 2006, the Fulcrum TV documentary "Da Vinci's Lost Code" was based on an idea and proposed book project by Simon Cox and G. Stephen Holmes.

Cox went on to co-author four A to Z series of books, with subjects comprising, Egypt, Atlantis, King Arthur & The Holy Grail and The Occult. Before these books were released, he compiled The Dan Brown Companion, for Mainstream Publishing in the UK.

Previous to being an author in his own right, Cox was a researcher within the ancient mysteries and alternate history genre. He worked as a primary researcher for such authors as, Graham Hancock, Robert Bauval, David Rohl, Graham Philips, Andrew Collins, amongst many others. He went on to be the Editor in Chief of the US newsstand magazine, Phenomena, employing many of the leading lights of the genre as contributors, before writing his first book and becoming a full time author. He has authored and co-authored some eight books as of January 2010. Several more book projects are set to follow in 2012. Cox has over 25 foreign language editions of his books and several of his publications reached the top 20 in various international non-fiction sales charts. In 2006 and 2007, Cox, along with authors Ian Robertson and Mark Oxbrow developed and put on the live show, "Rosslyn & The Grail" at the acclaimed Edinburgh Fringe Festival, with the 2006 run being officially declared a sell-out and gaining several excellent reviews. Cox remains a well known speaker and lecturer, as well as having undertaken several television and radio interviews and appearances, including the BBC quiz show, Battle of The Books, as well as spots on Sky News in the UK. Cox has also auditioned and filmed for several production companies and television stations as a presenter and program lead. His first two books were both adapted for documentary production and subsequently released on DVD, both also having been broadcast on US and international cable and satellite television stations on a number of occasions, with his Illuminating Angels & Demons production becoming a regular and popular show on both A&E and The History Channel in the United States.

Until late 2010, Cox was also the editor of the internet based magazine, Into The DUAT, where he maintained a popular blog. This project has apparently been put on ice whilst he plans to launch a new publishing imprint. His last book, published on 15 October 2009 in the UK and November 3rd 2009 in the US, was Decoding the Lost Symbol, an expose and facts behind the fiction guide to the last Dan Brown best selling thriller, The Lost Symbol, with the Cox publication appearing just a few weeks after the Dan Brown original.

Cox currently runs a UK based publishing, production and new media company, Henu Publications, working with Susan Davies. Cox is at present working on several new book and visual production projects as well as many other non genre related areas. Cox is a keen Rugby Union watcher, as well as a fan of Newcastle United Football Club. He currently lives in Bedford, UK.

Extract Taken From Wikipedia

More Info Related:

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2757

http://www.bertrand.pt/ficha/os-anos-desconhecidos-de-cristo?id=65977

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2672

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=4606

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=3271

http://www.livrarialeitura.pt/livro/cavaleiros-esplendor-e-crepusculo-os-emmanuel-bourassin/

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2572

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2751

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=49

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=1760

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2245

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2756

http://www.europa-america.pt/product_info.php?products_id=2747

http://www.bertrand.pt/ficha/os-templarios?id=64494

Marcadores:

books,

da vinci code,

europa-américa,

grail mysteries,

historical enigmas,

Leonardo Da Vinci,

Simon Cox

O Código Da Vinci

About The Novel:

The Da Vinci Code is a 2003 mystery-detective novel written by Dan Brown. It follows symbologist Robert Langdon and Sophie Neveu as they investigate a murder in Paris's Louvre Museum and discover a battle between the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei over the possibility of Jesus having been married to Mary Magdalene. The title of the novel refers to, among other things, the fact that the murder victim is found in the Grand Gallery of the Louvre, naked and posed like Leonardo da Vinci's famous drawing, the Vitruvian Man, with a cryptic message written beside his body and a pentacle drawn on his chest in his own blood.

The novel is part of the exploration of alternative religious history, whose central plot point is that the Merovingian kings of France were descendants from the bloodline of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene, ideas derived from Clive Prince's The Templar Revelation and books by Margaret Starbird. Chapter 60 of the book also references another book, The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail though Dan Brown has stated that this was not used as research material.

The book has provoked a popular interest in speculation concerning the Holy Grail legend and Magdalene's role in the history of Christianity. The book has been extensively denounced by many Christian denominations as an attack on the Roman Catholic Church. It has also been consistently criticized for its historical and scientific inaccuracies. The novel nonetheless became a worldwide bestseller that sold 80 million copies as of 2009[update][1] and has been translated into 44 languages. This makes it, as of 2010, the best selling English language novel of the 21st century and the second biggest selling novel of the 21st century in any language. Combining the detective, thriller, and conspiracy fiction genres, it is Brown's second novel to include the character Robert Langdon, the first being his 2000 novel Angels & Demons. In November 2004, Random House published a Special Illustrated Edition with 160 illustrations. In 2006, a film adaptation was released by Sony's Columbia Pictures.

Secret of the Holy Grail

In the novel Leigh Teabing explains to Sophie Neveu that the figure at the right hand of Jesus in Leonardo da Vinci's painting of "The Last Supper" is not the apostle John, but actually Mary Magdalene. Leigh Teabing says that the absence of a chalice in Leonardo's painting means Leonardo knew that Mary Magdalene was the actual Holy Grail and the bearer of Jesus' blood . Leigh Teabing goes on to explain that this idea is supported by the shape of the letter "V" that is formed by the bodily positions of Jesus and Mary, as "V" is the symbol for the sacred feminine. The absence of the Apostle John in the painting is explained by knowing that John is also referred to as "the Disciple Jesus loved", code for Mary Magdalene. The book also notes that the color scheme of their garments are inverted: Jesus wears a red tunic with royal blue cloak; John/Magdalene wears the opposite.

According to the novel, the secrets of the Holy Grail, as kept by the Priory of Sion are as follows:

The Holy Grail is not a physical chalice, but a woman, namely Mary Magdalene, who carried the bloodline of Christ.

The Old French expression for the Holy Grail, San gréal, actually is a play on Sang réal, which literally means "royal blood" in Old French.

The Grail relics consist of the documents that testify to the bloodline, as well as the actual bones of Mary Magdalene.

The Grail relics of Mary Magdalene were hidden by the Priory of Sion in a secret crypt, perhaps beneath Rosslyn Chapel.

The Church has suppressed the truth about Mary Magdalene and the Jesus bloodline for 2000 years. This is principally because they fear the power of the sacred feminine in and of itself and because this would challenge the primacy of Saint Peter as an apostle.

Mary Magdalene was of royal descent (through the Jewish House of Benjamin) and was the wife of Jesus, of the House of David. That she was a prostitute was slander invented by the Church to obscure their true relationship. At the time of the Crucifixion, she was pregnant. After the Crucifixion, she fled to Gaul, where she was sheltered by the Jews of Marseille. She gave birth to a daughter, named Sarah. The bloodline of Jesus and Mary Magdalene became the Merovingian dynasty of France.

The existence of the bloodline was the secret that was contained in the documents discovered by the Crusaders after they conquered Jerusalem in 1099 (see Kingdom of Jerusalem). The Priory of Sion and the Knights Templar were organized to keep the secret.

The secrets of the Grail are connected, according to the novel, to Leonardo Da Vinci's work as follows:

Leonardo was a member of the Priory of Sion and knew the secret of the Grail. The secret is in fact revealed in The Last Supper, in which no actual chalice is present at the table. The figure seated next to Christ is not a man, but a woman, his wife Mary Magdalene. Most reproductions of the work are from a later alteration that obscured her obvious female characteristics.

The androgyny of the Mona Lisa reflects the sacred union of male and female implied in the holy union of Jesus and Mary Magdalene. Such parity between the cosmic forces of masculine and feminine has long been a deep threat to the established power of the Church. The name Mona Lisa is actually an anagram for "Amon L'Isa", referring to the father and mother gods of Ancient Egyptian religion (namely Amun and Isis).

Extracts Taken From Wikipedia

More (related) Info:

http://www.danbrown.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dan_Brown

http://www.leonardo3.net/leonardo/home_eng.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonardo_da_Vinci

quinta-feira, 13 de outubro de 2011

segunda-feira, 10 de outubro de 2011

O Zohar (O Livro do Esplendor)

Extract Info On The Book (from Wikipedia):

The Zohar (Hebrew: זֹהַר, lit Splendor or Radiance) is the foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah.[1] It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah (the five books of Moses) and scriptural interpretations as well as material on Mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology. The Zohar contains a discussion of the nature of God, the origin and structure of the universe, the nature of souls, redemption, the relationship of Ego to Darkness and "true self" to "The Light of God," and the relationship between the "universal energy" and man. Its scriptural exegesis can be considered an esoteric form of the Rabbinic literature known as Midrash, which elaborates on the Torah.

The Zohar is mostly written in what has been described as an exalted, eccentric style of Aramaic, which was the day-to-day language of Israel in the Second Temple period (539 BC – 70 AD), was the original language of large sections of the biblical books of Daniel and Ezra, and is the main language of the Talmud.[2]

The Zohar first appeared in Spain in the 13th century, and was published by a Jewish writer named Moses de Leon. De Leon ascribed the work to Shimon bar Yochai, a rabbi of the 2nd century during the Roman persecution[3] who, according to Jewish legend,[4][5] hid in a cave for thirteen years studying the Torah and was inspired by the Prophet Elijah to write the Zohar. This accords with the traditional claim by adherents that Kabbalah is the concealed part of the Oral Torah.

While the traditional majority view in religious Judaism has been that the teachings of Kabbalah were revealed by God to Biblical figures such as Abraham and Moses and were then transmitted orally from the Biblical era until its redaction by Shimon ben Yochai, modern academic analysis of the Zohar, such as that by the 20th century religious historian Gershom Scholem, has theorized that De Leon was the actual author. The view of non-Orthodox Jewish denominations generally conforms to this latter view, and as such, most non-Orthodox Jews have long viewed the Zohar as pseudepigraphy and apocrypha while sometimes accepting that its contents may have meaning for modern Judaism. Jewish prayerbooks edited by non-Orthodox Jews may therefore contain excerpts from the Zohar and other kabbalistic works,[6] even if the editors do not literally believe that they are oral traditions from the time of Moses.

The modern evolutionary view according to the authentic (from the sages) wisdom of Kabbalah, interprets the Zohar as a technology for people who are seeking meaningful and practical answers about the meaning of their lives, the purpose of creation and existence and their relationships with the laws of nature. [7][8]

Contents

The Book of Zohar includes parts and chapters in conformance with the weekly chapters of the Torah:[15]

The Book of Beresheet (Genesis): Beresheet, Noach, Lech Lecha, Vayera, Chaiey Sarah, Toldot, Vayetze, Vayishlach, Vayeshev, Miketz, Vayigash, Vayichi.

The Book of Shemot (Exodus): Shemot, Vayera, Bo, Bashalach, Yitro, Mishpatim, Terumah (Safra de Tzniuta), Tetzaveh, Ki Tissa, Veyikahel, Pekudey.

The Book of Vayikra (Leviticus): Vayikra, Tzav, Shmini, Tazria, Metzura, Acharey, Kedushim, Emor, Ba Har, Bechukotay.

The Book of Bamidbar (Numbers): Bamidbar, Naso (Idra Raba), Baalotcha, Shlach Lecha, Korach, Chukat, Balak, Pinchas, Matot.

The Book of Devarim (Deuteronomy): Devarim, Ve Etchanen, Ekev, Reah, Shoftim, Ki Titze, Ki Tavo, Nitzavim, Vayelech, Ha’azinu (Idra Zuta), V'Zos HaBercha.

( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zohar )

Marcadores:

books,

cabala,

editorial estampa,

esoterism,

jewish esotericism,

jewish mysticism,

kabbalah,

kabbalah texts,

mysticism

Subscrever:

Mensagens (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

.jpg)