sexta-feira, 17 de fevereiro de 2012

Boyd Rice: The Vessel Of God - M. Janeiro: Porto do Graal

Info About "The Vessel Of God" Author:

Boyd Blake Rice (born December 16, 1956) is an American experimental sound/noise musician using the name of NON since the mid-1970s, archivist, actor, photographer, author, member of the Partridge Family Temple religious group, co-founder of the UNPOP art movement[1] and current staff writer for Modern Drunkard magazine.[2]

Biography

Rice became widely known through his involvement in V. Vale's RE/Search books. He is profiled in RE/Search #6/7: Industrial Culture Handbook[3] and Pranks!.[4] In Pranks, Rice described his experience in 1976 when he tried to give President Ford's wife, Betty Ford, a skinned sheep's head on a silver platter. In this interview, he emphasized the consensus nature of reality and the havoc that can be wreaked by refusing to play by the collective rules that dictate most people's perception of the external world.

In the mid-1980s Rice became close friends with Anton LaVey, founder and High Priest of the Church of Satan, and was made a Priest, then later a Magister in the Council of Nine of the Church. The two admired much of the same music and shared a similar misanthropic outlook. Each had been inspired by Might is Right in fashioning various works: LaVey in his seminal Satanic Bible and Rice in several recordings.

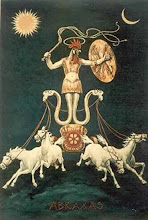

Rice's Social Darwinist outlook eventually led to him founding the Social Darwinist think tank called The Abraxas Foundation, along with co-founder Nikolas Schreck, named after the ancient Gnostic god Abraxas. The organization promotes authoritarianism, totalitarianism, misanthropism, elitism, is antidemocratic, and has some philosophical overlap with the Church of Satan. During an interview with Christian talk show host Bob Larson, Rice described the basic philosophy of the foundation as being "The strong rule the weak, and the clever rule the strong".[5]

Rice has documented the writings of Charles Manson in his role as contributing editor of The Manson File. Rice was a featured guest on Talk Back, a radio program hosted by the Evangelical Christian Bob Larson.[6] In total, Rice made five appearances on Larson's program.

Although Rice was sometimes reported to possess the world's largest Barbie collection, he confessed in a 2003 interview with Brian M. Clark to owning only a few.[7]

In 2000, along with Tracy Twyman, editor of Dagobert's Revenge, Rice filmed a special on the Rennes-le-Chateau for the program In Search of... on Fox television. (The segment was later included in the 2002 version of In Search of... on the Sci Fi Channel.) Rice has done extensive research into Gnosticism as well as Grail legends and Merovingian lore, sharing this research in Dagobert's Revenge and The Vessel of God.[8]

Rice was involved in creating a Tiki bar called Tiki Boyd's at the East Coast Bar in Denver, Colorado. Rice decorated the entire establishment out of his own pocket due to his fondness of Tiki culture, asking an open tab at the bar in return. Boyd has long expressed a love of Tiki culture, in contrast to the other elements of his public persona.[9]

Tiki Boyd's was given its name in his honor.[10] Due to disagreements between Rice and the owners, Rice pulled out of the deal and reclaimed all of his Tiki decorations. The future of the bar as it remains now is uncertain. Rice plans to re-establish another Tiki Bar elsewhere in Denver.[9]

Controversy

In 1989, Rice and Bob Heick of the American Front were photographed for Sassy Magazine wearing uniforms and brandishing knives. While Rice would later recall it as a prank, the photo has caused boycotts and protests at many of Rice's appearances. When asked if he regrets the photo, Rice stated, "I don't care. I don't think I ever made a wrong move. The bad stuff is just good. America loves its villains".[16]

This photograph was additionally published in the book Blood in the Face: The Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads, and the Rise of a New White Culture by James Ridgeway.[17]

More controversy has resulted because of Rice's appearance on Race and Reason,[18] a public-access television cable TV show hosted by white nationalist Tom Metzger. Boyd has claimed not to be a Nazi in numerous interviews[19][20] and many of his personal friends such as Rose McDowall have claimed he has never said anything racist nor endorsed Nazism.[21] Despite this individuals such as Stewart Home continue to claim that Boyd is a Nazi.[22] Boyd Rice is associated with Church of Satan founder Anton LaVey who was born Jewish[23] and has collaborated with Adam Parfrey[24] who is Jewish.[25]

On August 8, 1988, Boyd Rice was among the organizers and performers at a Satanic rally organized at the Strand Theater in San Francisco, which was locally heavily advertised and sold out, billed as the largest gathering of Satanists ever recorded. Rice appeared with the band Radio Werewolf as well as Zeena Lavey of the Church of Satan, and with the Secret Chiefs and Kris Force.[26]

Extracts Taken From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boyd_Rice

More Info:

http://www.thevesselofgod.com/

http://pt.scribd.com/doc/61070448/44/The-Vessel-of-God

http://pt.scribd.com/doc/61074660/Boyd-Rice-The-Vessel-of-God-II-Gnostic-Esoteric-Occult-and-Other-Writings

Marcadores:

books,

Boyd Rice,

esoterism,

gnosticism,

gnosticluciferianism,

grail mysteries,

M. Janeiro,

occultism,

portugraal,

templarism,

terra fria

segunda-feira, 13 de fevereiro de 2012

Non - Children Of The Black Sun (CD+DVD)

More Info:

http://mute.com/release/non-children-of-the-black-sun

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Children_of_the_Black_Sun

http://www.boydrice.com/discography/nondiscography.html

http://www.myspace.com/boydnonrice

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Boyd-Rice/109818112369494

NON MusicVideo From YouTube:

Marcadores:

alchemusic,

Boyd Rice,

cds,

dvds,

esoteric-occult music,

mute,

NON

Ain Soph – Ars Regia (Athanor Special Edition)

More Info:

http://www.arsregia.org/maintenance.php

http://www.myspace.com/ainsophroma

http://it-it.facebook.com/ainsoph.roma#!/ainsoph.roma?sk=info

The VisualMusics From YouTube:

sexta-feira, 27 de janeiro de 2012

segunda-feira, 23 de janeiro de 2012

sexta-feira, 13 de janeiro de 2012

Apocalypse Culture: Expanded and Revised Edition

Info On The Author:

Adam Parfrey (born 1957) is an American journalist, editor, and the publisher of Feral House books,[1] whose work in all three capacities frequently centers on unusual, extreme, or "forbidden" areas of knowledge.

Life

He was born in New York the son of actor Woodrow Parfrey (his mother, Rosa Ellovich, was Jewish, his father was not). He moved to Los Angeles, California in 1962. Upon graduating from Santa Monica High School, the young Parfrey enrolled at UCLA before transferring to UC, Santa Cruz where he studied theater and history without graduating. While at UCLA, he wrote for the student newspaper, the Daily Bruin, and later became co-editor. [2]

He collaborated on George Petros' Exit magazine.

Following a stint at the tabloid newspaper Idea Magazine, Parfrey returned to New York. In 1989 he started Feral House with $5,000.

He now lives in Port Townsend, Washington. Parfrey also publishes through Process Media, an imprint he established in 2005.

Controversy

Parfrey has been targeted on several occasions by fundamentalist Christian activists and by "concerned" individuals, who dislike the published material coming from Feral House. However, one of his goals is not merely to educate or entertain, but to unsettle and perhaps upset certain segments of the population. Parfrey has said that "upsetting people is a beautiful thing. Because it gets people to think beyond their last visit to 7-Eleven. There's a lot about this world to be upset about." [3]

Parfrey's penchant for upsetting people extends to what many would regard as dishonesty in promoting Feral House books. He promoted the second edition of Dark Mission[4][5] with the following sentence:

Authors Richard C. Hoagland and Mike Bara include a new chapter about the discoveries made by ex-Nazi scientist and NASA stalwart Wernher von Braun regarding what he termed "alternate gravitational solutions," or the rewriting of Newtonian physics into hyperdimensional spheres.

The chapter was not in fact in the book, and the false promo went uncorrected for 18 months.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Parfrey

More Info:

http://www.amazon.com/Apocalypse-Culture-Adam-Parfrey/dp/0922915059

Nihilism

Nihilism ( /ˈnaɪ.ɨlɪzəm/ or /ˈniː.ɨlɪzəm/; from the Latin nihil, nothing) is the philosophical doctrine suggesting the negation of one or more putatively meaningful aspects of life. Most commonly, nihilism is presented in the form of existential nihilism which argues that life is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value.[1] Moral nihilists assert that morality does not inherently exist, and that any established moral values are abstractly contrived. Nihilism can also take epistemological, metaphysical, or ontological forms, meaning respectively that, in some aspect, knowledge is not possible, or that contrary to popular belief, some aspect of reality does not exist as such.

The term nihilism is sometimes used in association with anomie to explain the general mood of despair at a perceived pointlessness of existence that one may develop upon realizing there are no necessary norms, rules, or laws.[2] Movements such as Futurism and deconstruction,[3] among others, have been identified by commentators as "nihilistic" at various times in various contexts.

Nihilism is also a characteristic that has been ascribed to time periods: for example, Jean Baudrillard and others have called postmodernity a nihilistic epoch,[4] and some Christian theologians and figures of religious authority have asserted that postmodernity[5] and many aspects of modernity[3] represent a rejection of theism, and that rejection of their theistic doctrine entails nihilism.

History

19th-century

Though the term nihilism was first popularized by the novelist Ivan Turgenev (1818–1883) in his novel "'Fathers and Sons,[6] it was first introduced into philosophical discourse by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743–1819). Jacobi used the term to characterize rationalism[7] and in particular Immanuel Kant's "critical" philosophy in order to carry out a reductio ad absurdum according to which all rationalism (philosophy as criticism) reduces to nihilism, and thus it should be avoided and replaced with a return to some type of faith and revelation. Bret W. Davis writes, for example, "The first philosophical development of the idea of nihilism is generally ascribed to Friedrich Jacobi, who in a famous letter criticized Fichte's idealism as falling into nihilism. According to Jacobi, Fichte’s absolutization of the ego (the 'absolute I' that posits the 'not-I') is an inflation of subjectivity that denies the absolute transcendence of God."[8] A related but oppositional concept is fideism, which sees reason as hostile and inferior to faith.

With the popularizing of the word nihilism by Turgenev, a new Russian political movement called the Nihilism movement adopted the term. They supposedly called themselves nihilists because nothing "that then existed found favor in their eyes."[9]

Kierkegaard

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_S%C3%B8ren_Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) posited an early form of nihilism which he referred to as levelling.[10] He saw levelling as the process of suppressing individuality to a point where the individual's uniqueness becomes non-existent and nothing meaningful in his existence can be affirmed:

Levelling at its maximum is like the stillness of death, where one can hear one's own heartbeat, a stillness like death, into which nothing can penetrate, in which everything sinks, powerless. One person can head a rebellion, but one person cannot head this levelling process, for that would make him a leader and he would avoid being levelled. Each individual can in his little circle participate in this levelling, but it is an abstract process, and levelling is abstraction conquering individuality.

—Søren Kierkegaard, The Present Age, translated by Alexander Dru with Foreword by Walter Kaufmann, p. 51-53

Kierkegaard, an advocate of a philosophy of life, generally argued against levelling and its nihilist consequence, although he believed it would be "genuinely educative to live in the age of levelling [because] people will be forced to face the judgement of [levelling] alone."[11] George Cotkin asserts Kierkegaard was against "the standardization and levelling of belief, both spiritual and political, in the nineteenth century [and he] opposed tendencies in mass culture to reduce the individual to a cipher of conformity and deference to the dominant opinion."[12] In his day, tabloids (like the Danish magazine Corsaren) and corrupt Christianity were instruments of levelling and contributed to the "reflective apathetic age" of 19th century Europe.[13] Kierkegaard argues that individuals who can overcome the levelling process are stronger for it and that it represents a step in the right direction towards "becoming a true self."[11][14] As we must overcome levelling[15], Hubert Dreyfus and Jane Rubin argue that Kierkegaard's interest, "in an increasingly nihilistic age, is in how we can recover the sense that our lives are meaningful".[16]

Note however that Kierkegaard's meaning of "nihilism" differs from the modern definition in the sense that, for Kierkegaard, levelling led to a life lacking meaning, purpose or value,[13] whereas the modern interpretation of nihilism posits that there was never any meaning, purpose or value to begin with.

Nietzsche

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_Friedrich_Nietzsche

Nihilism is often associated with the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who provided a detailed diagnosis of nihilism as a widespread phenomenon of Western culture. Though the notion appears frequently throughout Nietzsche's work, he uses the term in a variety of ways, with different meanings and connotations, both positive and negative. Karen Carr describes Nietzsche's characterization of nihilism "as a condition of tension, as a disproportion between what we want to value (or need) and how the world appears to operate."[17] When we find out that the world does not possess the objective value or meaning that we want it to have or have long since believed it to have, we find ourselves in a crisis.[18] Nietzsche asserts that with the decline of Christianity and the rise of physiological decadence, nihilism is in fact characteristic of the modern age,[19] though he implies that the rise of nihilism is still incomplete and that it has yet to be overcome.[20] Though the problem of nihilism becomes especially explicit in Nietzsche's notebooks (published posthumously), it is mentioned repeatedly in his published works and is closely connected to many of the problems mentioned there.

Nietzsche characterized nihilism as emptying the world and especially human existence of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value. This observation stems in part from Nietzsche's perspectivism, or his notion that "knowledge" is always by someone of some thing: it is always bound by perspective, and it is never mere fact.[21] Rather, there are interpretations through which we understand the world and give it meaning. Interpreting is something we can not go without; in fact, it is something we need. One way of interpreting the world is through morality, as one of the fundamental ways in which people make sense of the world, especially in regard to their own thoughts and actions. Nietzsche distinguishes a morality that is strong or healthy, meaning that the person in question is aware that he constructs it himself, from weak morality, where the interpretation is projected on to something external. Regardless of its strength, morality presents us with meaning, whether this is created or 'implanted,' which helps us get through life.[22] This is exactly why Nietzsche states that nihilism as "absolute valuelessness" or "nothing has meaning"[23] is dangerous, or even "the danger of dangers"[24]: it is through valuation that people survive and endure the danger, pain and hardships they face in life. The complete destruction of all meaning and all values would lead to an existence of apathy and stillness, where positive actions, affirmative actions, would be replaced by a state of reaction and destruction. This is the prophecy of "der letzte Mensch", the last man [25], the most despicable man, devoid of values, incapable of self-realization through creation of his own good and evil, devoid of any "will to power" (Wille zur Macht).

Nietzsche discusses Christianity, one of the major topics in his work, at length in the context of the problem of nihilism in his notebooks, in a chapter entitled 'European Nihilism'.[26] Here he states that the Christian moral doctrine provides people with intrinsic value, belief in God (which justifies the evil in the world) and a basis for objective knowledge. In this sense, in constructing a world where objective knowledge is possible, Christianity is an antidote against a primal form of nihilism, against the despair of meaninglessness. However, it is exactly the element of truthfulness in Christian doctrine that is its undoing: in its drive towards truth, Christianity eventually finds itself to be a construct, which leads to its own dissolution. It is therefore that Nietzsche states that we have outgrown Christianity "not because we lived too far from it, rather because we lived too close."[27] As such, the self-dissolution of Christianity constitutes yet another form of nihilism. Because Christianity was an interpretation that posited itself as the interpretation, Nietzsche states that this dissolution leads beyond skepticism to a distrust of all meaning.[28][29]

Stanley Rosen identifies Nietzsche's concept of nihilism with this situation of meaninglessness, where "everything is permitted." According to him, the loss of higher metaphysical values which existed in contrast with the base reality of the world or merely human ideas give rise to the idea that all human ideas are therefore valueless. Rejection of idealism thus results in nihilism, because only similarly transcendent ideals would live up to the previous standards that the nihilist still implicitly holds.[30] The inability for Christianity to serve as a source of valuating the world is reflected in Nietzsche's famous aphorism of the madman in the Gay Science.[31] The death of God, in particular the statement that "we killed him", is similar to the self-dissolution of Christian doctrine: due to the advances of the sciences, which for Nietzsche show that man is the product of evolution, that earth has no special place among the stars and that history is not progressive, the Christian notion of God can no longer serve as a basis for a morality.

One such reaction to the loss of meaning is what Nietzsche calls 'passive nihilism', which he recognises in the pessimistic philosophy of Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer's doctrine, which Nietzsche also refers to as Western Buddhism, advocates a separating oneself of will and desires in order to reduce suffering. Nietzsche characterises this ascetic attitude as a "will to nothingness," whereby life turns away from itself, as there is nothing of value to be found in the world. This mowing away of all value in the world is characteristic of the nihilist, although in this, the nihilist appears to be inconsistent[32]:

A nihilist is a man who judges of the world as it is that it ought not to be, and of the world as it ought to be that it does not exist. According to this view, our existence (action, suffering, willing, feeling) has no meaning: the pathos of 'in vain' is the nihilists' pathos — at the same time, as pathos, an inconsistency on the part of the nihilists.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, KSA 12:9 [60], taken from The Will to Power, section 585, translated by Walter Kaufmann

Nietzsche's relation to the problem of nihilism is a complex one. He approaches the problem of nihilism as a deeply personal one, stating that this problem of the modern world is a problem that has "become conscious" in him.[33] Furthermore, he emphasises both the danger of nihilism and the possibilities it offers, as seen in his statement that "I praise, I do not reproach, [nihilism's] arrival. I believe it is one of the greatest crises, a moment of the deepest self-reflection of humanity. Whether man recovers from it, whether he becomes master of this crisis, is a question of his strength!"[34] According to Nietzsche, it is only when nihilism is overcome that a culture can have a true foundation upon which to thrive. He wished to hasten its coming only so that he could also hasten its ultimate departure.[19]

He states that there is at least the possibility of another type of nihilist in the wake of Christianity's self-dissolution, one that does not stop after the destruction of all value and meaning and succumb to the following nothingness. This alternate, 'active' nihilism on the other hand destroys to level the field for constructing something new. This form of nihilism is characterized by Nietzsche as "a sign of strength,"[35] a wilful destruction of the old values to wipe the slate clean and lay down one's own beliefs and interpretations, contrary to the passive nihilism that resigns itself with the decomposition of the old values. This wilful destruction of values and the overcoming of the condition of nihilism by the constructing of new meaning, this active nihilism could be related to what Nietzsche elsewhere calls a 'free spirit'[36] or the Übermensch from Thus Spoke Zarathustra and the Antichrist, the model of the strong individual who posits his own values and lives his life as if it were his own work of art.

Heidegger's interpretation of Nietzsche

Many postmodern thinkers who investigated the problem of nihilism as put forward by Nietzsche, were influenced by Martin Heidegger’s interpretation of Nietzsche. It is only recently that Heidegger’s influence on nihilism research by Nietzsche has faded.[37] As early as the 1930s, Heidegger was giving lectures on Nietzsche’s thought.[38] Given the importance of Nietzsche’s contribution to the topic of nihilism, Heidegger's influential interpretation of Nietzsche is important for the historical development of the term nihilism.

Heidegger's method of researching and teaching Nietzsche is explicitly his own. He does not specifically try to present Nietzsche as Nietzsche. He rather tries to incorporate Nietzsche's thoughts into his own philosophical system of Being, Time and Dasein.[39] In his Nihilism as Determined by the History of Being (1944–46),[40] Heidegger tries to understand Nietzsche’s nihilism as trying to achieve a victory through the devaluation of the, until then, highest values. The principle of this devaluation is, according to Heidegger, the Will to Power. The Will to Power is also the principle of every earlier valuation of values.[41] How does this devaluation occur and why is this nihilistic? One of Heidegger’s main critiques on philosophy is that philosophy, and more specifically metaphysics, has forgotten to discriminate between investigating the notion of a Being (Seiende) and Being (Sein). According to Heidegger, the history of Western thought can be seen as the history of metaphysics. And because metaphysics has forgotten to ask about the notion of Being (what Heidegger calls Seinsvergessenheit), it is a history about the destruction of Being. That is why Heidegger calls metaphysics nihilistic.[42] This makes Nietzsche’s metaphysics not a victory over nihilism, but a perfection of it.[43]

Heidegger, in his interpretation of Nietzsche, has been inspired by Ernst Jünger. Many references to Jünger can be found in Heidegger’s lectures on Nietzsche. For example, in a letter to the rector of Freiburg University of November 4, 1945, Heidegger, inspired by Jünger, tries to explain the notion of “God is dead” as the “reality of the Will to Power.” Heidegger also praises Jünger for defending Nietzsche against a too biological or anthropological reading during the Third Reich.[44]

A number of important postmodernist thinkers were influenced by Heidegger's interpretation of Nietzsche. Gianni Vattimo points at a back and forth movement in European thought, between Nietzsche and Heidegger. During the 1960s, a Nietzschean 'renaissance' began, culminating in the work of Mazzino Montinari and Giorgio Colli. They began work on a new and complete edition of Nietzsche's collected works, making Nietzsche more accessible for scholarly research. Vattimo explains that with this new edition of Colli and Montinari, a critical reception of Heidegger's interpretation of Nietzsche began to take shape. Like other contemporary French and Italian philosophers, Vattimo does not want, or only partially wants, to rely on Heidegger for understanding Nietzsche. On the other hand, Vattimo judges Heidegger's intentions authentic enough to keep pursuing them.[45] Philosophers who Vattimo exemplifies as a part of this back and forth movement are French philosophers Deleuze, Foucault and Derrida. Italian philosophers of this same movement are Cacciari, Severino and himself.[46] Habermas, Lyotard and Rorty are also philosophers who are influenced by Heidegger’s interpretation of Nietzsche.[47]

Postmodernism

Postmodern and poststructuralist thought question the very grounds on which Western cultures have based their 'truths': absolute knowledge and meaning, a 'decentralization' of authorship, the accumulation of positive knowledge, historical progress, and certain ideals and practices of humanism and the Enlightenment.

Jacques Derrida, whose deconstruction is perhaps most commonly labeled nihilistic, did not himself make the nihilistic move that others have claimed. Derridean deconstructionists argue that this approach rather frees texts, individuals or organizations from a restrictive truth, and that deconstruction opens up the possibility of other ways of being.[48] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, for example, uses deconstruction to create an ethics of opening up Western scholarship to the voice of the subaltern and to philosophies outside of the canon of western texts.[49] Derrida himself built a philosophy based upon a 'responsibility to the other'.[50] Deconstruction can thus be seen not as a denial of truth, but as a denial of our ability to know truth (it makes an epistemological claim compared to nihilism's ontological claim).

Lyotard argues that, rather than relying on an objective truth or method to prove their claims, philosophers legitimize their truths by reference to a story about the world which is inseparable from the age and system the stories belong to, referred to by Lyotard as meta-narratives. He then goes on to define the postmodern condition as one characterized by a rejection both of these meta-narratives and of the process of legitimation by meta-narratives. "In lieu of meta-narratives we have created new language-games in order to legitimize our claims which rely on changing relationships and mutable truths, none of which is privileged over the other to speak to ultimate truth." This concept of the instability of truth and meaning leads in the direction of nihilism, though Lyotard stops short of embracing the latter.

Postmodern theorist Jean Baudrillard wrote briefly of nihilism from the postmodern viewpoint in Simulacra and Simulation. He stuck mainly to topics of interpretations of the real world over the simulations of which the real world is composed. The uses of meaning was an important subject in Baudrillard's discussion of nihilism:

The apocalypse is finished, today it is the precession of the neutral, of forms of the neutral and of indifference…all that remains, is the fascination for desertlike and indifferent forms, for the very operation of the system that annihilates us. Now, fascination (in contrast to seduction, which was attached to appearances, and to dialectical reason, which was attached to meaning) is a nihilistic passion par excellence, it is the passion proper to the mode of disappearance. We are fascinated by all forms of disappearance, of our disappearance. Melancholic and fascinated, such is our general situation in an era of involuntary transparency.

—Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, "On Nihilism", trans. 1995

Forms of nihilism

Moral nihilism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moral_nihilism

Moral nihilism, also known as ethical nihilism, is the meta-ethical view that morality does not exist as something inherent to objective reality; therefore no action is necessarily preferable to any other. For example, a moral nihilist would say that killing someone, for whatever reason, is not inherently right or wrong. Other nihilists may argue not that there is no morality at all, but that if it does exist, it is a human and thus artificial construction, wherein any and all meaning is relative for different possible outcomes. As an example, if someone kills someone else, such a nihilist might argue that killing is not inherently a bad thing, bad independently from our moral beliefs, only that because of the way morality is constructed as some rudimentary dichotomy, what is said to be a bad thing is given a higher negative weighting than what is called good: as a result, killing the individual was bad because it did not let the individual live, which was arbitrarily given a positive weighting. In this way a moral nihilist believes that all moral claims are false.

Existential nihilism

Existential nihilism is the belief that life has no intrinsic meaning or value. With respect to the universe, existential nihilism posits that a single human or even the entire human species is insignificant, without purpose and unlikely to change in the totality of existence. The meaninglessness of life is largely explored in the philosophical school of existentialism.

Epistemological nihilism

Nihilism of an epistemological form can be seen as an extreme form of skepticism in which all knowledge is denied.[51]

Metaphysical nihilism

Metaphysical nihilism is the philosophical theory that there might be no objects at all, i.e. that there is a possible world in which there are no objects at all; or at least that there might be no concrete objects at all, so even if every possible world contains some objects, there is at least one that contains only abstract objects.

An extreme form of metaphysical nihilism is commonly defined as the belief that existence itself does not exist.[52][53] One way of interpreting such a statement would be: It is impossible to distinguish 'existence' from 'non-existence' as there are no objective qualities, and thus a reality, that one state could possess in order to discern between the two. If one cannot discern existence from its negation, then the concept of existence has no meaning; or in other words, does not 'exist' in any meaningful way. 'Meaning' in this sense is used to argue that as existence has no higher state of reality, which is arguably its necessary and defining quality, existence itself means nothing. It could be argued that this belief, once combined with epistemological nihilism, leaves one with an all-encompassing nihilism in which nothing can be said to be real or true as such values do not exist. A similar position can be found in solipsism; however, in this viewpoint the solipsist affirms whereas the nihilist would deny the self. Both these positions are forms of anti-realism.[citation needed]

Mereological nihilism

Mereological nihilism (also called compositional nihilism) is the position that objects with proper parts do not exist (not only objects in space, but also objects existing in time do not have any temporal parts), and only basic building blocks without parts exist, and thus the world we see and experience full of objects with parts is a product of human misperception (i.e., if we could see clearly, we would not perceive compositive objects).

Political nihilism

Political nihilism, a branch of nihilism, follows the characteristic nihilist's rejection of non-rationalized or non-proven assertions; in this case the necessity of the most fundamental social and political structures, such as government, family, law and law enforcement. The Nihilist movement in 19th century Russia espoused a similar doctrine. Political nihilism is rather different from other forms of nihilism, and is actually more like a form of Utilitarianism.

Radical nihilism

Radical nihilism is the belief that there, in the last instance, is not given a foundation for knowledge, ethics nor justice, and not even this lack of foundation can serve as a starting point for (or rejection of) knowledge, ethics or justice. Radical nihilism turns in the light of the missing universal, objective, and ahistorical certainties, towards the historically and culturally transmitted possibilities of cognition and moral/political action, well aware that the true and the good are in the last instants based on faith.

Extensive Extract Taken From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nihilism

More Sites About Nihilism:

http://www.nihil.org/

http://www.counterorder.com/

http://www.anus.com/

The term nihilism is sometimes used in association with anomie to explain the general mood of despair at a perceived pointlessness of existence that one may develop upon realizing there are no necessary norms, rules, or laws.[2] Movements such as Futurism and deconstruction,[3] among others, have been identified by commentators as "nihilistic" at various times in various contexts.

Nihilism is also a characteristic that has been ascribed to time periods: for example, Jean Baudrillard and others have called postmodernity a nihilistic epoch,[4] and some Christian theologians and figures of religious authority have asserted that postmodernity[5] and many aspects of modernity[3] represent a rejection of theism, and that rejection of their theistic doctrine entails nihilism.

History

19th-century

Though the term nihilism was first popularized by the novelist Ivan Turgenev (1818–1883) in his novel "'Fathers and Sons,[6] it was first introduced into philosophical discourse by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743–1819). Jacobi used the term to characterize rationalism[7] and in particular Immanuel Kant's "critical" philosophy in order to carry out a reductio ad absurdum according to which all rationalism (philosophy as criticism) reduces to nihilism, and thus it should be avoided and replaced with a return to some type of faith and revelation. Bret W. Davis writes, for example, "The first philosophical development of the idea of nihilism is generally ascribed to Friedrich Jacobi, who in a famous letter criticized Fichte's idealism as falling into nihilism. According to Jacobi, Fichte’s absolutization of the ego (the 'absolute I' that posits the 'not-I') is an inflation of subjectivity that denies the absolute transcendence of God."[8] A related but oppositional concept is fideism, which sees reason as hostile and inferior to faith.

With the popularizing of the word nihilism by Turgenev, a new Russian political movement called the Nihilism movement adopted the term. They supposedly called themselves nihilists because nothing "that then existed found favor in their eyes."[9]

Kierkegaard

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_S%C3%B8ren_Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) posited an early form of nihilism which he referred to as levelling.[10] He saw levelling as the process of suppressing individuality to a point where the individual's uniqueness becomes non-existent and nothing meaningful in his existence can be affirmed:

Levelling at its maximum is like the stillness of death, where one can hear one's own heartbeat, a stillness like death, into which nothing can penetrate, in which everything sinks, powerless. One person can head a rebellion, but one person cannot head this levelling process, for that would make him a leader and he would avoid being levelled. Each individual can in his little circle participate in this levelling, but it is an abstract process, and levelling is abstraction conquering individuality.

—Søren Kierkegaard, The Present Age, translated by Alexander Dru with Foreword by Walter Kaufmann, p. 51-53

Kierkegaard, an advocate of a philosophy of life, generally argued against levelling and its nihilist consequence, although he believed it would be "genuinely educative to live in the age of levelling [because] people will be forced to face the judgement of [levelling] alone."[11] George Cotkin asserts Kierkegaard was against "the standardization and levelling of belief, both spiritual and political, in the nineteenth century [and he] opposed tendencies in mass culture to reduce the individual to a cipher of conformity and deference to the dominant opinion."[12] In his day, tabloids (like the Danish magazine Corsaren) and corrupt Christianity were instruments of levelling and contributed to the "reflective apathetic age" of 19th century Europe.[13] Kierkegaard argues that individuals who can overcome the levelling process are stronger for it and that it represents a step in the right direction towards "becoming a true self."[11][14] As we must overcome levelling[15], Hubert Dreyfus and Jane Rubin argue that Kierkegaard's interest, "in an increasingly nihilistic age, is in how we can recover the sense that our lives are meaningful".[16]

Note however that Kierkegaard's meaning of "nihilism" differs from the modern definition in the sense that, for Kierkegaard, levelling led to a life lacking meaning, purpose or value,[13] whereas the modern interpretation of nihilism posits that there was never any meaning, purpose or value to begin with.

Nietzsche

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_Friedrich_Nietzsche

Nihilism is often associated with the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who provided a detailed diagnosis of nihilism as a widespread phenomenon of Western culture. Though the notion appears frequently throughout Nietzsche's work, he uses the term in a variety of ways, with different meanings and connotations, both positive and negative. Karen Carr describes Nietzsche's characterization of nihilism "as a condition of tension, as a disproportion between what we want to value (or need) and how the world appears to operate."[17] When we find out that the world does not possess the objective value or meaning that we want it to have or have long since believed it to have, we find ourselves in a crisis.[18] Nietzsche asserts that with the decline of Christianity and the rise of physiological decadence, nihilism is in fact characteristic of the modern age,[19] though he implies that the rise of nihilism is still incomplete and that it has yet to be overcome.[20] Though the problem of nihilism becomes especially explicit in Nietzsche's notebooks (published posthumously), it is mentioned repeatedly in his published works and is closely connected to many of the problems mentioned there.

Nietzsche characterized nihilism as emptying the world and especially human existence of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value. This observation stems in part from Nietzsche's perspectivism, or his notion that "knowledge" is always by someone of some thing: it is always bound by perspective, and it is never mere fact.[21] Rather, there are interpretations through which we understand the world and give it meaning. Interpreting is something we can not go without; in fact, it is something we need. One way of interpreting the world is through morality, as one of the fundamental ways in which people make sense of the world, especially in regard to their own thoughts and actions. Nietzsche distinguishes a morality that is strong or healthy, meaning that the person in question is aware that he constructs it himself, from weak morality, where the interpretation is projected on to something external. Regardless of its strength, morality presents us with meaning, whether this is created or 'implanted,' which helps us get through life.[22] This is exactly why Nietzsche states that nihilism as "absolute valuelessness" or "nothing has meaning"[23] is dangerous, or even "the danger of dangers"[24]: it is through valuation that people survive and endure the danger, pain and hardships they face in life. The complete destruction of all meaning and all values would lead to an existence of apathy and stillness, where positive actions, affirmative actions, would be replaced by a state of reaction and destruction. This is the prophecy of "der letzte Mensch", the last man [25], the most despicable man, devoid of values, incapable of self-realization through creation of his own good and evil, devoid of any "will to power" (Wille zur Macht).

Nietzsche discusses Christianity, one of the major topics in his work, at length in the context of the problem of nihilism in his notebooks, in a chapter entitled 'European Nihilism'.[26] Here he states that the Christian moral doctrine provides people with intrinsic value, belief in God (which justifies the evil in the world) and a basis for objective knowledge. In this sense, in constructing a world where objective knowledge is possible, Christianity is an antidote against a primal form of nihilism, against the despair of meaninglessness. However, it is exactly the element of truthfulness in Christian doctrine that is its undoing: in its drive towards truth, Christianity eventually finds itself to be a construct, which leads to its own dissolution. It is therefore that Nietzsche states that we have outgrown Christianity "not because we lived too far from it, rather because we lived too close."[27] As such, the self-dissolution of Christianity constitutes yet another form of nihilism. Because Christianity was an interpretation that posited itself as the interpretation, Nietzsche states that this dissolution leads beyond skepticism to a distrust of all meaning.[28][29]

Stanley Rosen identifies Nietzsche's concept of nihilism with this situation of meaninglessness, where "everything is permitted." According to him, the loss of higher metaphysical values which existed in contrast with the base reality of the world or merely human ideas give rise to the idea that all human ideas are therefore valueless. Rejection of idealism thus results in nihilism, because only similarly transcendent ideals would live up to the previous standards that the nihilist still implicitly holds.[30] The inability for Christianity to serve as a source of valuating the world is reflected in Nietzsche's famous aphorism of the madman in the Gay Science.[31] The death of God, in particular the statement that "we killed him", is similar to the self-dissolution of Christian doctrine: due to the advances of the sciences, which for Nietzsche show that man is the product of evolution, that earth has no special place among the stars and that history is not progressive, the Christian notion of God can no longer serve as a basis for a morality.

One such reaction to the loss of meaning is what Nietzsche calls 'passive nihilism', which he recognises in the pessimistic philosophy of Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer's doctrine, which Nietzsche also refers to as Western Buddhism, advocates a separating oneself of will and desires in order to reduce suffering. Nietzsche characterises this ascetic attitude as a "will to nothingness," whereby life turns away from itself, as there is nothing of value to be found in the world. This mowing away of all value in the world is characteristic of the nihilist, although in this, the nihilist appears to be inconsistent[32]:

A nihilist is a man who judges of the world as it is that it ought not to be, and of the world as it ought to be that it does not exist. According to this view, our existence (action, suffering, willing, feeling) has no meaning: the pathos of 'in vain' is the nihilists' pathos — at the same time, as pathos, an inconsistency on the part of the nihilists.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, KSA 12:9 [60], taken from The Will to Power, section 585, translated by Walter Kaufmann

Nietzsche's relation to the problem of nihilism is a complex one. He approaches the problem of nihilism as a deeply personal one, stating that this problem of the modern world is a problem that has "become conscious" in him.[33] Furthermore, he emphasises both the danger of nihilism and the possibilities it offers, as seen in his statement that "I praise, I do not reproach, [nihilism's] arrival. I believe it is one of the greatest crises, a moment of the deepest self-reflection of humanity. Whether man recovers from it, whether he becomes master of this crisis, is a question of his strength!"[34] According to Nietzsche, it is only when nihilism is overcome that a culture can have a true foundation upon which to thrive. He wished to hasten its coming only so that he could also hasten its ultimate departure.[19]

He states that there is at least the possibility of another type of nihilist in the wake of Christianity's self-dissolution, one that does not stop after the destruction of all value and meaning and succumb to the following nothingness. This alternate, 'active' nihilism on the other hand destroys to level the field for constructing something new. This form of nihilism is characterized by Nietzsche as "a sign of strength,"[35] a wilful destruction of the old values to wipe the slate clean and lay down one's own beliefs and interpretations, contrary to the passive nihilism that resigns itself with the decomposition of the old values. This wilful destruction of values and the overcoming of the condition of nihilism by the constructing of new meaning, this active nihilism could be related to what Nietzsche elsewhere calls a 'free spirit'[36] or the Übermensch from Thus Spoke Zarathustra and the Antichrist, the model of the strong individual who posits his own values and lives his life as if it were his own work of art.

Heidegger's interpretation of Nietzsche

Many postmodern thinkers who investigated the problem of nihilism as put forward by Nietzsche, were influenced by Martin Heidegger’s interpretation of Nietzsche. It is only recently that Heidegger’s influence on nihilism research by Nietzsche has faded.[37] As early as the 1930s, Heidegger was giving lectures on Nietzsche’s thought.[38] Given the importance of Nietzsche’s contribution to the topic of nihilism, Heidegger's influential interpretation of Nietzsche is important for the historical development of the term nihilism.

Heidegger's method of researching and teaching Nietzsche is explicitly his own. He does not specifically try to present Nietzsche as Nietzsche. He rather tries to incorporate Nietzsche's thoughts into his own philosophical system of Being, Time and Dasein.[39] In his Nihilism as Determined by the History of Being (1944–46),[40] Heidegger tries to understand Nietzsche’s nihilism as trying to achieve a victory through the devaluation of the, until then, highest values. The principle of this devaluation is, according to Heidegger, the Will to Power. The Will to Power is also the principle of every earlier valuation of values.[41] How does this devaluation occur and why is this nihilistic? One of Heidegger’s main critiques on philosophy is that philosophy, and more specifically metaphysics, has forgotten to discriminate between investigating the notion of a Being (Seiende) and Being (Sein). According to Heidegger, the history of Western thought can be seen as the history of metaphysics. And because metaphysics has forgotten to ask about the notion of Being (what Heidegger calls Seinsvergessenheit), it is a history about the destruction of Being. That is why Heidegger calls metaphysics nihilistic.[42] This makes Nietzsche’s metaphysics not a victory over nihilism, but a perfection of it.[43]

Heidegger, in his interpretation of Nietzsche, has been inspired by Ernst Jünger. Many references to Jünger can be found in Heidegger’s lectures on Nietzsche. For example, in a letter to the rector of Freiburg University of November 4, 1945, Heidegger, inspired by Jünger, tries to explain the notion of “God is dead” as the “reality of the Will to Power.” Heidegger also praises Jünger for defending Nietzsche against a too biological or anthropological reading during the Third Reich.[44]

A number of important postmodernist thinkers were influenced by Heidegger's interpretation of Nietzsche. Gianni Vattimo points at a back and forth movement in European thought, between Nietzsche and Heidegger. During the 1960s, a Nietzschean 'renaissance' began, culminating in the work of Mazzino Montinari and Giorgio Colli. They began work on a new and complete edition of Nietzsche's collected works, making Nietzsche more accessible for scholarly research. Vattimo explains that with this new edition of Colli and Montinari, a critical reception of Heidegger's interpretation of Nietzsche began to take shape. Like other contemporary French and Italian philosophers, Vattimo does not want, or only partially wants, to rely on Heidegger for understanding Nietzsche. On the other hand, Vattimo judges Heidegger's intentions authentic enough to keep pursuing them.[45] Philosophers who Vattimo exemplifies as a part of this back and forth movement are French philosophers Deleuze, Foucault and Derrida. Italian philosophers of this same movement are Cacciari, Severino and himself.[46] Habermas, Lyotard and Rorty are also philosophers who are influenced by Heidegger’s interpretation of Nietzsche.[47]

Postmodernism

Postmodern and poststructuralist thought question the very grounds on which Western cultures have based their 'truths': absolute knowledge and meaning, a 'decentralization' of authorship, the accumulation of positive knowledge, historical progress, and certain ideals and practices of humanism and the Enlightenment.

Jacques Derrida, whose deconstruction is perhaps most commonly labeled nihilistic, did not himself make the nihilistic move that others have claimed. Derridean deconstructionists argue that this approach rather frees texts, individuals or organizations from a restrictive truth, and that deconstruction opens up the possibility of other ways of being.[48] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, for example, uses deconstruction to create an ethics of opening up Western scholarship to the voice of the subaltern and to philosophies outside of the canon of western texts.[49] Derrida himself built a philosophy based upon a 'responsibility to the other'.[50] Deconstruction can thus be seen not as a denial of truth, but as a denial of our ability to know truth (it makes an epistemological claim compared to nihilism's ontological claim).

Lyotard argues that, rather than relying on an objective truth or method to prove their claims, philosophers legitimize their truths by reference to a story about the world which is inseparable from the age and system the stories belong to, referred to by Lyotard as meta-narratives. He then goes on to define the postmodern condition as one characterized by a rejection both of these meta-narratives and of the process of legitimation by meta-narratives. "In lieu of meta-narratives we have created new language-games in order to legitimize our claims which rely on changing relationships and mutable truths, none of which is privileged over the other to speak to ultimate truth." This concept of the instability of truth and meaning leads in the direction of nihilism, though Lyotard stops short of embracing the latter.

Postmodern theorist Jean Baudrillard wrote briefly of nihilism from the postmodern viewpoint in Simulacra and Simulation. He stuck mainly to topics of interpretations of the real world over the simulations of which the real world is composed. The uses of meaning was an important subject in Baudrillard's discussion of nihilism:

The apocalypse is finished, today it is the precession of the neutral, of forms of the neutral and of indifference…all that remains, is the fascination for desertlike and indifferent forms, for the very operation of the system that annihilates us. Now, fascination (in contrast to seduction, which was attached to appearances, and to dialectical reason, which was attached to meaning) is a nihilistic passion par excellence, it is the passion proper to the mode of disappearance. We are fascinated by all forms of disappearance, of our disappearance. Melancholic and fascinated, such is our general situation in an era of involuntary transparency.

—Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, "On Nihilism", trans. 1995

Forms of nihilism

Moral nihilism

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moral_nihilism

Moral nihilism, also known as ethical nihilism, is the meta-ethical view that morality does not exist as something inherent to objective reality; therefore no action is necessarily preferable to any other. For example, a moral nihilist would say that killing someone, for whatever reason, is not inherently right or wrong. Other nihilists may argue not that there is no morality at all, but that if it does exist, it is a human and thus artificial construction, wherein any and all meaning is relative for different possible outcomes. As an example, if someone kills someone else, such a nihilist might argue that killing is not inherently a bad thing, bad independently from our moral beliefs, only that because of the way morality is constructed as some rudimentary dichotomy, what is said to be a bad thing is given a higher negative weighting than what is called good: as a result, killing the individual was bad because it did not let the individual live, which was arbitrarily given a positive weighting. In this way a moral nihilist believes that all moral claims are false.

Existential nihilism

Existential nihilism is the belief that life has no intrinsic meaning or value. With respect to the universe, existential nihilism posits that a single human or even the entire human species is insignificant, without purpose and unlikely to change in the totality of existence. The meaninglessness of life is largely explored in the philosophical school of existentialism.

Epistemological nihilism

Nihilism of an epistemological form can be seen as an extreme form of skepticism in which all knowledge is denied.[51]

Metaphysical nihilism

Metaphysical nihilism is the philosophical theory that there might be no objects at all, i.e. that there is a possible world in which there are no objects at all; or at least that there might be no concrete objects at all, so even if every possible world contains some objects, there is at least one that contains only abstract objects.

An extreme form of metaphysical nihilism is commonly defined as the belief that existence itself does not exist.[52][53] One way of interpreting such a statement would be: It is impossible to distinguish 'existence' from 'non-existence' as there are no objective qualities, and thus a reality, that one state could possess in order to discern between the two. If one cannot discern existence from its negation, then the concept of existence has no meaning; or in other words, does not 'exist' in any meaningful way. 'Meaning' in this sense is used to argue that as existence has no higher state of reality, which is arguably its necessary and defining quality, existence itself means nothing. It could be argued that this belief, once combined with epistemological nihilism, leaves one with an all-encompassing nihilism in which nothing can be said to be real or true as such values do not exist. A similar position can be found in solipsism; however, in this viewpoint the solipsist affirms whereas the nihilist would deny the self. Both these positions are forms of anti-realism.[citation needed]

Mereological nihilism

Mereological nihilism (also called compositional nihilism) is the position that objects with proper parts do not exist (not only objects in space, but also objects existing in time do not have any temporal parts), and only basic building blocks without parts exist, and thus the world we see and experience full of objects with parts is a product of human misperception (i.e., if we could see clearly, we would not perceive compositive objects).

Political nihilism

Political nihilism, a branch of nihilism, follows the characteristic nihilist's rejection of non-rationalized or non-proven assertions; in this case the necessity of the most fundamental social and political structures, such as government, family, law and law enforcement. The Nihilist movement in 19th century Russia espoused a similar doctrine. Political nihilism is rather different from other forms of nihilism, and is actually more like a form of Utilitarianism.

Radical nihilism

Radical nihilism is the belief that there, in the last instance, is not given a foundation for knowledge, ethics nor justice, and not even this lack of foundation can serve as a starting point for (or rejection of) knowledge, ethics or justice. Radical nihilism turns in the light of the missing universal, objective, and ahistorical certainties, towards the historically and culturally transmitted possibilities of cognition and moral/political action, well aware that the true and the good are in the last instants based on faith.

Extensive Extract Taken From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nihilism

More Sites About Nihilism:

http://www.nihil.org/

http://www.counterorder.com/

http://www.anus.com/

terça-feira, 27 de dezembro de 2011

Gnosticism in Modern Times

Gnosticism includes a variety of religious movements, mostly Christian in nature, in the ancient Hellenistic society around the Mediterranean. Although origins are disputed, the period of activity for most of these movements flourished from approximately the time of the founding of Christianity until the 4th century when the writings and activities of groups deemed heretical or pagan were actively suppressed. The only information available on these movements for many centuries was the characterizations of those writing against them, and the few quotations preserved in such works.

The late 19th century saw the publication of popular sympathetic studies making use of recently rediscovered source materials. In this period there was also revival of the Gnostic religious movement in France. The emergence of the Nag Hammadi library in 1945, greatly increased the amount of source material available. Its translation into English and other modern languages in 1977, resulted in a wide dissemination, and has as a result had observable influence on several modern figures, and upon modern Western culture in general. This article attempts to summarize those modern figures and movements that have been influenced by Gnosticism, both prior and subsequent to the Nag Hammadi discovery.

Contents

1 Late 19th century

1.1 Charles William King

1.2 Madame Blavatsky

1.3 G. R. S. Mead

1.4 The Gnostic Church revival in France

2 Early to mid-20th century

2.1 Carl Jung

2.1.1 The Jung Codex

2.2 French Gnostic Church split, reintegration, and continuation

2.3 Modern sex magic associated with Gnosticism

2.3.1 Modern sex magic brought to South America

2.4 The Gnostic Society

3 Mid-20th century

3.1 Ecclesia Gnostica

3.1.1 Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum

3.2 Samael Aun Weor and sex magic in South America

3.3 Hans Jonas

3.4 Eric Voegelin's anti-modernist 'gnostic thesis'

4 The Nag Hammadi Library

5 Gnosticism in popular culture

6 See also

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Late 19th century

Source materials were discovered in the 18th century. In 1769 the Bruce Codex was brought to England from Upper Egypt by the famous Scottish traveller Bruce, and subsequently bequeathed to the care of the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Sometime prior to 1785 The Askew Codex (aka Pistis Sophia) was bought by the British Museum from the heirs of Dr. Askew. Pistis Sophia text and Latin translation of the Askew Codex by M. G. Schwartze published in 1851. Although discovered in 1896 the Coptic Berlin Codex (aka. the Akhmim Codex), is not 'rediscovered' until the 20th century.

Charles William King

Charles William King was a British writer and collector of ancient gemstones with magical inscriptions. His collection was sold because of his failing eyesight, and was presented in 1881 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. King was recognized as one of the greatest authorities on gems.[1]

In The Gnostics and their Remains (1864, 1887 2nd ed.) King sets out to show that rather than being a Western heresy, the origins of Gnosticism are to be found in the East, specifically in Buddhism. This theory was embraced by Blavatsky, who argued that it was plausible, but rejected by GRS Mead. According to Mead, King's work "lacks the thoroughness of the specialist."[2]

Madame Blavatsky

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, co-founder of the Theosophical Society, wrote extensively on Gnostic ideas. A compilation of her writings on Gnosticism is over 270 pages long.[3] The first edition of King's The Gnostics and Their Remains was repeatedly cited as a source and quoted in Isis Unveiled.

G. R. S. Mead

G. R. S. Mead became a member of Blavatsky's Theosophical Society in 1884. He left the teaching profession in 1889 to become Blavatsky's private secretary, which he was until her death in 1891. Mead's interest in Gnosticism was likely awakened by Blavatsky who discussed it at length in Isis Unveiled.[4]

In 1890-1 Mead published a serial article on Pistis Sophia in Lucifer magazine, the first English translation of that work. In an article in 1891, Mead argues for the recovery of the literature and thought of the West at a time when Theosophy was largely directed to the East. Saying that this recovery of Western antique traditions is a work of interpretation and "the rendering of tardy justice to pagans and heretics, the reviled and rejected pioneers of progress..."[5] This was the direction his own work was to take.

The first edition of his translation of Pistis Sophia appeared in 1896. From 1896-8 Mead published another serial article in the same periodical, "Among the Gnostics of the First Two Centuries," that laid the foundation for his monumental compendium Fragments of a Faith Forgotten in 1900. Mead serially published translations from the Corpus Hermeticum from 1900-05. The next year he published Thrice-Greatest Hermes a massive comprehensive three volume treatise. His series Echoes of the Gnosis was published in 12 booklets in 1908. By the time he left the Theosophical Society in 1909, he had published many influential translations, commentaries, and studies of ancient Gnostic texts. "Mead made Gnosticism accessible to the intelligent public outside of academia..."[6] Mead's work has had and continues to have widespread influence.[7]

The Gnostic Church revival in France

After a series of visions and archival finds of Cathar-related documents, a librarian named Jules-Benoît Stanislas Doinel du Val-Michel (aka Jules Doinel) establishes the Eglise Gnostique (French: Gnostic Church). Founded on extant Cathar documents with the Gospel of John and strong influence of Simonian and Valentinian cosmology, the church was officially established in the autumn of 1890 in Paris, France. Doinel declared it "the era of Gnosis restored." Liturgical services were based on Cathar rituals. Clergy was both male and female, having male bishops and female "sophias."[8][9]

Doinel resigned and converted to Roman Catholicism in 1895, one of many duped by Léo Taxil's anti-masonic hoax, writing Lucifer Unmasked a book attacking freemasonry. Taxil unveiled the hoax in 1897. Doinel was readmitted to the Gnostic church as a bishop in 1900.

Early to mid-20th century

Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung evinced a special interest in Gnosticism from at least 1912, when he wrote enthusiastically about the topic in a letter to Freud. After what he called his own 'encounter with the unconscious,' Jung sought for external evidence of this kind of experience. He found such evidence in Gnosticism, and also in Alchemy, which he saw as a continuation of Gnostic thought, and of which more source material was available.[10] In his study of the Gnostics, Jung made extensive use of the work of GRS Mead. Jung visited Mead in London to thank him for the Pistis Sophia, the two corresponded, and Mead visited Jung in Zürich.[11]

Jung saw the Gnostics not as syncretic schools of mixed theological doctrines, but as genuine visionaries, and saw their imagery not as myths but as records of inner experience.[12] He wrote that "The explanation of Gnostic ideas 'in terms of themselves,' i.e., in terms of their historical foundations, is futile, for in that way they are reduced only to their less developed forestages but not understood in their actual significance."[13] Instead, he worked to understand and explain Gnosticism from a psychological standpoint. (See Jungian interpretation of religion.) While providing something of an ancient mirror of his work, Jung saw "his psychology not as a contemporary version of Gnosticism, but as a contemporary counterpart to it."[14]

Jung reported a series of experiences in the winter of 1916-17 that inspired him to write Septem Sermones ad Mortuos (Latin: Seven Sermons to the Dead).[15][16]

The Jung Codex

Through the efforts of Gilles Quispel, the Jung Codex was the first codex brought to light from the Nag Hammadi Library. It was purchased by the Jung Institute and ceremonially presented to Jung in 1953 because of his great interest in the ancient Gnostics.[17] First publication of translations of Nag Hammadi texts in 1955 with the Jung Codex by H. Puech, Gilles Quispel, and W. Van Unnik.

French Gnostic Church split, reintegration, and continuation

Jean Bricaud had been involved with the Eliate Church of Carmel of Eugene Vintras, the remnants of Fabré-Palaprat's l'Église Johannites des Chretiens Primitif (Johannite Church of the Primitive Christians), and the Martinist Order before being consecrated a bishop of l'Église Gnostique in 1901. In 1907 Bricaud established a church body that combined all of these, becoming patriarch under the name Tau Jean II. The impetus for this was to use the Western Rite. Briefly called the Eglise Catholique Gnostique (Gnostic Catholic Church), the name was changed to Eglise Gnostique Universelle (Universal Gnostic Church, EGU) in 1908. The close ties between the church and Martinism were formalized in 1911. Bricaud received consecration in the Villate line of Apostolic Succession in 1919.[8][9]

The original church body founded by Doinel continued under the name Eglise Gnostique du France (Gnostic Church of France) until it was disbanded in favor of the EGU in 1926. The EGU continued until 1960 when it was disbanded by Robert Amberlain (Tau Jean III) in favor of Eglise Gnostique Apostolique that he had founded in 1958.[18] It is active in France (including Martinique), the Ivory Coast, and the Midwestern United States.

Modern sex magic associated with Gnosticism

The use of the term 'gnostic' by sexual magic groups is a modern phenomenon. Hugh Urban concludes that, "despite the very common use of sexual symbolism throughout Gnostic texts, there is little evidence (apart from the accusations of the early church) that the Gnostics engaged in any actual performance of sexual rituals, and certainly not anything resembling modern sexual magic."[19] Modern sexual magic began with Paschal Beverly Randolph.[20] The connection to Gnosticism came by way of the French Gnostic Church with its close ties to the strong esoteric current in France, being part of the same highly interconnected milieu of esoteric societies and orders from which the most influential of sexual magic orders arose, the Ordo Templi Orientis (Order of Oriental Templars, OTO).

Theodor Reuss founded the OTO as an umbrella occult organization with sexual magic at its core.[21] After Reuss came into contact with French Gnostic Church leaders at a Masonic and Spiritualist conference in 1908, he founded Die Gnostische Katholische Kirche (the Gnostic Catholic Church), under the auspices of the OTO.[8] Reuss subsequently dedicated the OTO to the promulgation of Crowley's philosophy of Thelema. It is for this church body, called in Latin the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica (EGC), that Aleister Crowley wrote the Ecclesiæ Gnosticæ Catholicæ Canon Missæ ("Canon of the Mass of the Gnostic Catholic Church"),[22] the central ritual of the OTO that is now commonly called the Gnostic Mass.

Modern sex magic brought to South America

Arnoldo Krumm-Heller traveled in occult circles at the turn of the century where he studied with notable figures such as Gérard Encausse of the Martinist Order and Franz Hartmann of the OTO. In 1910 he founded the Iglesia Gnostica (Gnostic Church) in Mexico. Not finding as much success as he hoped for, he moved through Latin America before settling in Brazil. There he founded the Fraternidad de Rosacruz Antiqua (Fraternity of the Ancient Rosicrucians), following Randolph's usage. Krumm-Heller moved back to Germany in 1920, where he made contact with Aleister Crowley. Krumm-Heller kept a low profile through World War II, but when he was able to travel again after the war, he resumed contact with his Latin America students. Between that time and his death in 1949, Krumm-Heller encountered and subsequently mentored Victor Rodriguez who would subsequently take the name Samael Aun Weor.[23] Weor states that Krumm-Heller taught a form of Sexual Magic without ejaculation that would become the core of his own teachings.

The Gnostic Society

The Gnostic Society, was founded for the study of gnosticism in 1928 and incorporated in 1939 by Theosophists James Morgan Pryse and his brother John Pryse in Los Angeles.[24][25] Since 1963 it has been under the direction of Stephan Hoeller and operates in association with the Ecclesia Gnostica. Initially begun as an archive for a usenet newsgroup circa 1993, the Gnosis Archive expanded beyond that purpose. It was the first web site to offer historic and source materials on Gnosticism, and continues to do so.

Mid-20th century

Ecclesia Gnostica

Established in 1953 by the Most Rev. Richard Duc de Palatine in England under the name 'the Pre-nicene Gnostic Catholic Church', the Ecclesia Gnostica (Latin: "Church of Gnosis" or "Gnostic Church") is said to represent 'the English Gnostic tradition', although it has ties to, and has been influenced by, the French Gnostic church tradition. It is affiliated with the Gnostic Society, an organization dedicated to the study of Gnosticism. The presiding bishop is the Rt. Rev. Stephan A. Hoeller, who has written extensively on Gnosticism.[15][24]

Centered in Los Angeles, the Ecclesia Gnostica has parishes and educational programs of the Gnostic Society spanning the Western US and also in the Kingdom of Norway.[24][25] The lectionary and liturgical calendar of the Ecclesia Gnostica have been widely adopted by subsequent Gnostic churches, as have the liturgical services in use by the church, though in somewhat modified forms.

Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum

The Ecclesia Gnostica Mysteriorum (EGM), commonly known as "the Church of Gnosis" or "the Gnostic Sanctuary," was initially established in Palo Alto by bishop Rosamonde Miller as a parish of the Ecclesia Gnostica, but soon became an independent body with emphasis on the divine feminine. The Gnostic Sanctuary is now located in Mountain View, California. [24][25] The EGM also claims a distinct lineage of Mary Magdalene from a surviving tradition in France.[26]

Samael Aun Weor and sex magic in South America

Victor Rodriguez left the FRA after the death of Krumm Heller. He reports an experience of being called to his new mission by the venerable white lodge (associated with Theosophy). Weor taught a "New Gnosis," consisting of Sexual Magic without ejaculation he called the Arcanum AZF. For him it is "the synthesis of all religions, schools and sects." Moving through Latin America, he finally settled in Mexico where he founded the Movimiento Gnostico Cristiano Universal (MGCU) (Universal Gnostic Christian Movement), then subsequently founded the Iglesia Gnostica Cristiana Universal (Universal Gnostic Christian Church) and the Associacion Gnostica de Estudios Antropologicos Culturales y Cientificos (AGEAC) (Gnostic Association of Scientific, Cultural and Anthropological Studies) to spread his teachings.[27]

The MGCU became defunct by the time of Weor's death in December 1977. However, his disciples subsequently formed new organizations to spread Weor's teachings, under the umbrella term 'the International Gnostic Movement'. These organizations are currently very active via the Internet and have centers established in Latin America, the US, Australia, and Europe.[28]

Hans Jonas

The philosopher Hans Jonas wrote extensively on Gnosticism, interpreting it from an existentialist viewpoint. For some time, his study The Gnostic Religion: The message of the alien God and the beginnings of Christianity published in 1958, was widely held to be a pivotal work, and it is as a result of his efforts that the Syrian-Egyptian/Persian division of Gnosticism came to be widely used within the field. The second edition, published in 1963, included the essay “Gnosticism, Existentialism, and Nihilism.”

Eric Voegelin's anti-modernist 'gnostic thesis'

In the 1950s, Eric Voegelin entered into an academic debate concerning the classification of modernity following Karl Löwith's 1949 Meaning in History: the Theological Implications of the Philosophy of History; and Jacob Taubes's 1947 Abendländishe Eschatologie. In this context, Voegelin put forward his "gnosticism thesis": criticizing modernity by identifying an "immanentist eschatology" as the "gnostic nature" of modernity. Differing with Löwith, he did not criticize eschatology as such, but rather the immanentization which he described as a "pneumopathological" deformation. Voegelin's gnosticism thesis became popular in neo-conservative and cold war political thought.[29]

The Nag Hammadi Library

Main article: Nag Hammadi Library

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nag_Hammadi_Library

Gnosticism in popular culture

Main article: Gnosticism in popular culture

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnosticism_in_popular_culture

Gnosticism has seen something of a resurgence in popular culture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. This may be related, certainly, to the sudden availability of Gnostic texts to the reading public, following the emergence of the Nag Hammadi library.

See also

Gnostic Association of Anthropological, Cultural and Scientific Studies

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnostic_Association_of_Anthropological,_Cultural_and_Scientific_Studies

teaching the doctrine of Samael Aun Weor

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samael_Aun_Weor

Gnostic church

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnostic_church

Gnostic saint

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gnostic_saint

Notes

1.^ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

2.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 8-9

3.^ Hoeller (2002) p. 167

4.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 8

5.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 56-7

6.^ Hoeller (2002) p. 170

7.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 31-2

8.^ a b c Pearson, J. (2007) p. 47

9.^ a b Hoeller (2002) p. 176-8

10.^ Segal (1995) p. 26

11.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 1, 30-1

12.^ Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 30

13.^ Jung (1977) p. 652

14.^ Segal (1995) p. 30

15.^ a b Goodrick-Clarke (2005) p. 31

16.^ Hoeller (1989) p. 7

17.^ Jung (1977) p. 671

18.^ Pearson, J. (2007) p. 131

19.^ Urban (2006) p. 36 note 68

20.^ Urban (2006) p. 36

21.^ Greer (2003) p. 221-2

22.^ The Equinox III:1 (1929) p. 247

23.^ Dawson (2007) p. 55-57

24.^ a b c d Pearson, B. (2007) p. 240

25.^ a b c Smith (1995) p. 206

26.^ Keizer, Lewis (2000). The Wandering Bishops: Apostles of a New Spirituality. St. Thomas Press. pp. 48. http://www.hometemple.org/WanBishWeb%20Complete.pdf.

27.^ Dawson (2007) p. 54-60

28.^ Dawson (2007) p. 60-65

29.^ Weiss (2000)

References

Crowley, Aleister (2007). The Equinox vol. III no. 1. San Francisco: Weiser. ISBN 9781578633531.

Dawson, Andrew (2007). New era, new religions: religious transformation in contemporary Brazil. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754654339.

Goodrick-Clarke, Clare (2005). G. R. S. Mead and the Gnostic Quest. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 155643572x.

Greer, John Micheal (2003). The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. St. Paul: Llewellyn. ISBN 1567183360.

Hoeller, Stephan (1989). The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead. Quest Books. ISBN 083560568X.

Hoeller, Stephan. Gnosticism: New light on the ancient tradition of inner knowing. Quest Books.

Jung, Carl Gustav (1977). The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, NJ: Bollingen (Princeton University). ISBN 0710082916.

Mead, GRS (1906 (2nd ed.)). Fragments of a Faith Forgotten. Theosophical Society.

Pearson, Birger (2007). Ancient Gnosticism: Traditions and Literature. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800632588.

Pearson, Joanne (2007). Wicca and the Christian Heritage. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415254140.

Segal, Robert (1995). "Jung's Fascination with Gnosticism". In Segal, Robert. The Allure of Gnosticism: the Gnostic experience in Jungian psychology and contemporary culture. Open Court. pp. 26–38. ISBN 0812692780.

Smith, Richard (1995). "The revival of ancient Gnosis". In Segal, Robert. The Allure of Gnosticism: the Gnostic experience in Jungian psychology and contemporary culture. Open Court. pp. 206. ISBN 0812692780.

Urban, Hugh B. (2006). Magia Sexualis: Sex, Magic, and Liberation in modern Western esotericism. University of California. ISBN 0520247760.

Weiss, Gilbert (2000). "Between gnosis and anamnesis--European perspectives on Eric Voegelin". The Review of Politics 62 (4): 753–776. doi:10.1017/S003467050004273X. 65964268.

Wasserstrom, Steven M. (1999). Religion after religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University. ISBN 0691005400.

External links