A solar deity (also sun god/dess) is a sky deity who represents the Sun, or an aspect of it, usually by its perceived power and strength. Solar deities and sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. Hence, many beliefs have formed around this worship, such as the "missing sun" found in many cultures.

Contents

- 1 Overview

- 2 Solar myth

- 3 Solar barge and sun chariot

- 4 Male and female

- 5 Missing sun

- 6 See also

- 7 References

- 8 Bibliography

- 9 External links

Overview

The Neolithic concept of a solar barge, the sun as traversing the sky in a boat, is found in the later myths of ancient Egypt, with Ra and Horus. Earlier Egyptian myths imply that the sun is within the lioness, Sekhmet, at night and can be seen reflected in her eyes or that it is within the cow, Hathor during the night, being reborn each morning as her son (bull).

Mesopotamian Shamash plays an important role during the Bronze Age, and "my Sun" is eventually used as an address to royalty. Similarly, South American cultures have a tradition of Sun worship, as with the Incan Inti. Svarog is the Slavic god sun and spirit of fire.

Proto-Indo-European religion has a solar chariot, the sun as traversing the sky in a chariot.[citation needed] In Germanic mythology this is Sol, in Vedic Surya, and in Greek Helios (occasionally referred to as Titan) and (sometimes) as Apollo.

During the Roman Empire, a festival of the birth of the Unconquered Sun (or Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) was celebrated on the winter solstice—the "rebirth" of the sun—which occurred on December 25 of the Julian calendar. In late antiquity, the theological centrality of the sun in some Imperial religious systems suggest a form of a “solar monotheism.” The religious commemorations on December 25 were replaced under Christian domination of the Empire with the birthday of Christ.[1]

Africa

The Tiv people consider the Sun to be the son of the supreme being Awondo and the Moon Awondo's daughter. The Barotse tribe believes that the Sun is inhabited by the sky god Nyambi and the Moon is his wife. Even where the sun god is equated with the supreme being, in some African mythologies he or she does not have any special functions or privileges as compared to other deities. The Ancient Egyptian god of creation, Amun is also believed to reside inside the sun. So is the Akan creator deity, Nyame and the Dogon deity of creation, Nommo.

Aztec mythology

In Aztec mythology, Tonatiuh (Nahuatl: Ollin Tonatiuh, "Movement of the Sun") was the sun god. The Aztec people considered him the leader of Tollan (heaven). He was also known as the fifth sun, because the Aztecs believed that he was the sun that took over when the fourth sun was expelled from the sky. According to their cosmology, each sun was a god with its own cosmic era. According to the Aztecs, they were still in Tonatiuh's era. According to the Aztec creation myth, the god demanded human sacrifice as tribute and without it would refuse to move through the sky. It is said that 20,000 people were sacrificed each year to Tonatiuh and other gods, though this number is thought to be inflated either by the Aztecs, who wanted to inspire fear in their enemies, or the Spaniards, who wanted to vilify the Aztecs. The Aztecs were fascinated by the sun and carefully observed it, and had a solar calendar similar to that of the Maya. Many of today's remaining Aztec monuments have structures aligned with the sun.[2]

In the Aztec calendar, Tonatiuh is the lord of the thirteen days from 1 Death to 13 Flint. The preceding thirteen days are ruled over by Chalchiuhtlicue, and the following thirteen by Tlaloc.

Buddhism

In Buddhist cosmology, the bodhisattva of the Sun is known as Ri Gong Ri Guang Pu Sa (The Bright Solar Bodhisattva of the Solar Palace) / Ri Gong Ri Guang Tian Zi (The Bright Solar Prince of the Solar Palace) / Ri Gong Ri Guang Zun Tian Pu Sa (The Greatly Revered Bright Solar Prince of the Solar Palace / one of the 20 or 24 guardian devas). In Sanskrit, He is known as Suryaprabha. He is usually depicted with Yue Gong Yue Guang Pu Sa (The Bright Lunar Bodhisattva of the Lunar Palace) / Yue Gong Yue Guang Tian Zi ( The Bright Lunar Prince of the Lunar Palace) / Yue Gong Yue Guang Zun Tian Pu Sa (The Greatly Revered Bright Lunar Prince of the Lunar Palace / one of the 20 or 24 guardian devas known as Candraprabha in Sanskrit. With Yao Shi Fo / Bhaisajyaguru Buddha (Medicine Buddha), these two bodhisattvas create the Dong Fang San Sheng or the Three Holy Sages of the East.

Chinese mythology

In Chinese mythology (cosmology), there were originally ten suns in the sky, who were all brothers. They were supposed to emerge one at a time as commanded by the Jade Emperor. They were all very young and loved to fool around. Once they decided to all go into the sky to play, all at once. This made the world too hot for anything to grow. A hero named Hou Yi shot down nine of them with a bow and arrow to save the people of the earth. He is still honored this very day. In another myth, the solar eclipse was caused by the magical dog of heaven biting off a piece of the sun. The referenced event is said to have occurred around 2,160BCE. There was a tradition in China to make lots of loud celebratory sounds during a solar eclipse to scare the sacred "dog" away. The Deity of the Sun in Chinese mythology is Ri Gong Tai Yang Xing Jun (Tai Yang Gong / Grandfather Sun) or Star Lord of the Solar Palace, Lord of the Sun. In some mythologies, Tai Yang Xing Jun is believed to be Hou Yi. Tai Yang Xing Jun is usually depicted with the Star Lord of the Lunar Palace, Lord of the Moon, Yue Gong Tai Yin Xing Jun (Tai Yin Niang Niang / Lady Tai Yin).

Christianity

Christ is associated with the Sun through Christmas, which occurs at the time of the Winter solstice. Many astro-theologians point out a connection between many of the supposed events in the New Testament to the phenomena of the sun which makes the biblical Jesus more of a solar riddle.

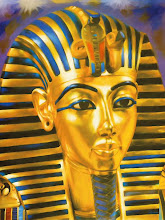

Ancient Egypt

Sun worship was prevalent in ancient Egyptian religion. The earliest deities associated with the sun are all goddesses: Wadjet, Sekhmet, Hathor, Nut, Bast, Bat, and Menhit. First Hathor, and then Isis, give birth to and nurse Horus and Ra. Hathor the horned-cow is one of the 12 daughters of Ra, gifted with joy and is a wet-nurse to Horus.

The Sun's movement across the sky represents a struggle between the Pharaoh's soul and an avatar of Osiris. Ra travels across the sky in his solar-boat; at dawn he drives away the demon Apep of darkness. The "solarisation" of several local gods (Hnum-Re, Min-Re, Amon-Re) reaches its peak in the period of the fifth dynasty.

Rituals to the god Amun who became identified with the sun god Ra were often carried out on the top of temple pylons. A Pylon mirrored the hieroglyph for 'horizon' or akhet, which was a depiction of two hills "between which the sun rose and set",[3] associated with recreation and rebirth. On the first Pylon of the temple of Isis at Philae, the pharaoh is shown slaying his enemies in the presence of Isis, Horus and Hathor. In the eighteenth dynasty, Akhenaten changed the polytheistic religion of Egypt to a monotheistic one, Atenism of the solar-disk and is the first recorded state monotheism. All other deities were replaced by the Aten, including Amun-Ra, the reigning sun god of Akhenaten's own region. Unlike other deities, the Aten did not have multiple forms. His only image was a disk—a symbol of the sun.

Soon after Akhenaten's death, worship of the traditional deities was reestablished by the religious leaders (Ay the High-Priest of Amen-Ra, mentor of Tutankhaten/Tutankhamen) who had adopted the Aten during the reign of Akhenaten.

Hinduism

The Ādityas are one of the principal deities of the Vedic classical Hinduism belonging to Solar class. In the Vedas, numerous hymns are dedicated to Mitra, Varuna, Savitr etc.

Even the Gayatri mantra, which is regarded as one of the most sacred of the Vedic hymns is dedicated to Savitr, one of the principal Ādityas. The Adityas are a group of solar deities, from the Brahmana period numbering twelve. The ritual of sandhyavandanam, performed by Hindus, is an elaborate set of hand gestures and body movements, designed to greet and revere the Sun.

The sun god in Hinduism is an ancient and revered deity. In later Hindu usage, all the Vedic Ādityas lost identity and metamorphosed into one composite deity, Surya, the Sun. The attributes of all other Ādityas merged into that of Surya and the names of all other Ādityas became synonymous with, or epithets of, Surya.

The Ramayana has Rama as a descendant of the Surya, thus belonging to the Suryavansha or the clan of the Sun. The Mahabharata describes one of its warrior heroes, Karna, as being the son of the Pandava mother Kunti and Surya.

The sun god is said to be married to the goddess Ranaadeh, also known as Sanjnya. She is depicted in dual form, being both sunlight and shadow, personified. The goddess is revered in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

The charioteer of Surya is Aruna, who is also personified as the redness that accompanies the sunlight in dawn and dusk. The sun god is driven by a seven-horsed Chariot depicting the seven days of the week.

In India, at Konark, in the state of Odisha, a temple is dedicated to Surya. The Konark Sun Temple has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Surya is the most prominent of the navagrahas or nine celestial objects of the Hindus. Navagrahas can be found in almost all Hindu temples. There are further temples dedicated to Surya, one in Arasavilli, Srikakulam District in AndhraPradesh, one in Gujarat at Modhera and another in Rajasthan. The temple at Arasavilli was constructed in such a way that on the day of Radhasaptami, the sun's rays directly fall on the feet of the Sri Suryanarayana Swami, the deity at the temple.

Chhath (Hindi: छठ, also called Dala Chhath) is an ancient Hindu festival dedicated to Surya, the chief solar deity, unique to Bihar, Jharkhand and the Terai. This major festival is also celebrated in the northeast region of India, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Chhattisgarh. Hymns to the sun can be found in the Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism. Practiced in different parts of India, the worship of the sun has been described in the Rigveda. There is another festival called Sambha-Dasami, which is celebrated in the state of Odisha for the surya.

The Gurjars (or Gujjars), were Sun-worshipers and are described as devoted to the feet of the sun god Surya. Their copper-plate grants bear an emblem of the Sun and on their seals too, this symbol is depicted.[4]

Indonesian mythology

Solar gods have a stronger presence in Indonesian mythology. In some cases the Sun is revered as a "father" or "founder" of the tribe. This may apply for the whole tribe or only for the royal and ruling families. This practise is more common in Australia and on the island of Timor, where the tribal leaders are seen as direct heirs to the sun god.

Some of the initiation rites include the second reincarnation of the rite's subject as a "son of the Sun", through a symbolic death and a rebirth in the form of a Sun. These rituals hint that the Sun may have an important role in the sphere of funerary beliefs. Watching the Sun's path has given birth to the idea in some societies that the deity of the Sun descends in to the underworld without dying and is capable of returning afterward. This is the reason for the Sun being associated with functions such as guide of the deceased tribe members to the underworld, as well as with revival of perished. The Sun is a mediator between the planes of the living and the dead.

Theosophy

The primary local deity in Theosophy is the Solar Logos, "the consciousness of the sun".[5]

Solar myth

Three theories exercised great influence on nineteenth and early twentieth century mythography, beside the Tree worship of Mannhardt and the Totemism of J. F. McLennan, the "Sun myth" of Alvin Boyd Kuhn and Max Müller.

R. F. Littledale criticized the Sun myth theory when he illustrated that Max Müller on his own principles was himself only a Solar myth, whilst Alfred Lyall delivered a still stronger attack on the same theory and its assumption that tribal gods and heroes, such as those of Homer, were mere reflections of the Sun myth by proving that the gods of certain Rajput clans were really warriors who founded the clans not many centuries ago, and were the ancestors of the present chieftains.[6]

Solar barge and sun chariot

A "solar barge" (also "solar bark", "solar barque", "solar boat" and "sun boat") is a mythological representation of the sun riding in a boat. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter-long vessel that was sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. This boat was rediscovered in May 1954 when archeologist Kamal el-Mallakh and inspector Zaki Nur found two ditches sealed off by about 40 blocks weighing 17 to 20 tonnes each. This boat was disassembled into 1,224 pieces and took over 10 years to reassemble. A nearby museum was built to house this boat.[7]

Other sun boats were found in Egypt dating to different pharonic dynasties.[8]

Examples include:

Examples include:

Male and female

Among modern English speakers, solar deities are popularly thought of as male counterparts of the lunar deity (usually female); however, sun goddesses are found on every continent (e.g. Amaterasu in Japanese belief) paired with male lunar deities. Among the earliest records of human beliefs, the early goddesses of the Egyptian pantheon carried a sun above their head as a symbol of dignity (as daughters of Ra). The sun was a major aspect of Egyptian symbols and hieroglyphs, all the lunar deities of that pantheon were male deities. The cobra (of Pharaoh Son of Ra), the lioness (daughter of Ra), the cow (daughter of Ra), the dominant symbols of the most ancient Egyptian deities, carried their relationship to the sun atop their heads; they were female and their cults remained active throughout the history of the culture. Later a sun god (Aten) was established in the eighteenth dynasty on top of the other solar deities, before the "aberration" was stamped out and the old pantheon re-established. When male deities became associated with the sun in that culture, they began as the offspring of a mother (except Ra, King of the Gods who gave birth to himself).

Some mythologists, such as Brian Branston, Patricia Monaghan and Janet McCrickard, contend that sun goddesses are as common as, or even more common, worldwide than their male counterparts. They also claim that the belief that solar deities are primarily male is linked to the fact that a few better known mythologies (such as those of late classical Greece and late Roman mythology) rarely break from this rule, although closer examination of the earlier myths of those cultures reveal a very different distribution than the contemporary popular belief. The dualism of sun/male/light and moon/female/darkness is found in many (but not all) late southern traditions in Europe that derive from Orphic and Gnostic philosophies.

In Germanic mythology the Sun is female and the Moon is male. The corresponding Old English name is Siȝel [ˈsɪjel], continuing Proto-Germanic *Sôwilô or *Saewelô. The Old High German Sun goddess is Sunna. In the Norse traditions, every day, Sól rode through the sky on her chariot, pulled by two horses named Arvak and Alsvid. Sól also was called Sunna and Frau Sunne, from which are derived the words: Sun and Sunday.

Other cultures that have sun goddesses include: The Lithuanians and Latvians (Saule), the Finns (Päivätär, Beiwe) and the related Hungarians (Xatel-Ekwa) and the Slavic peoples (Solntse). Sun goddesses are found around the world; in Arabia (Al-Lat), Australia (Bila, Walo), India (Bisal-Mariamna, Bomong, Kn Sgni) and Sri Lanka (Pattini); among the Hittites (Wurusemu), Egyptians (Sekhmet) and Babylonians (Shapash); in Native America, among the Cherokee (Unelanuhi), Natchez (Wal Sil), Inuit (Malina) and Miwok (Hekoolas).

Missing sun

The missing sun is a theme in the myths of many cultures,[citation needed] sometimes including the themes of imprisonment, exile, or death. The missing sun is often used to explain various natural phenomena, including the disappearance of the sun at night, shorter days during the winter, and solar eclipses.

Some other tales are similar, such as the Sumerian story of the goddess Inanna's descent into the underworld. These may have parallel themes, but do not fit in this motif unless they concern a solar deity.

In late Egyptian mythology, Ra passes through Duat (the underworld) every night. Apep has to be defeated in the darkness hours for Ra and his solar barge to emerge in the east each morning.

In Japanese mythology, the sun goddess Amaterasu is startled by the behavior of her brother Susanoo and hides in a cave, plunging the world into darkness until she is willing to emerge. It has been suggested that the story is allegorical, symbolising that the sun goddess hiding in a cave is a metaphor for the sun exhibiting quiet periods such as the Maunder Minimum. This allegory has been used in literature such as Masks of the Lost Kings.[12]

In Norse mythology, the gods Odin and Tyr both have attributes of a sky father, and they are doomed to be devoured by wolves (Fenrir and Garm, respectively) at Ragnarok. Sól, the Norse sun goddess, will be devoured by the wolf Skoll.

In Hindu astronomy, Rahu and Ketu ate the sun or moon to cause lunars and solar eclipses. In later, more scientific years, their names were given to the Lunar nodes.

See also

Mesopotamian Shamash plays an important role during the Bronze Age, and "my Sun" is eventually used as an address to royalty. Similarly, South American cultures have a tradition of Sun worship, as with the Incan Inti. Svarog is the Slavic god sun and spirit of fire.

Proto-Indo-European religion has a solar chariot, the sun as traversing the sky in a chariot.[citation needed] In Germanic mythology this is Sol, in Vedic Surya, and in Greek Helios (occasionally referred to as Titan) and (sometimes) as Apollo.

During the Roman Empire, a festival of the birth of the Unconquered Sun (or Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) was celebrated on the winter solstice—the "rebirth" of the sun—which occurred on December 25 of the Julian calendar. In late antiquity, the theological centrality of the sun in some Imperial religious systems suggest a form of a “solar monotheism.” The religious commemorations on December 25 were replaced under Christian domination of the Empire with the birthday of Christ.[1]

Africa

The Tiv people consider the Sun to be the son of the supreme being Awondo and the Moon Awondo's daughter. The Barotse tribe believes that the Sun is inhabited by the sky god Nyambi and the Moon is his wife. Even where the sun god is equated with the supreme being, in some African mythologies he or she does not have any special functions or privileges as compared to other deities. The Ancient Egyptian god of creation, Amun is also believed to reside inside the sun. So is the Akan creator deity, Nyame and the Dogon deity of creation, Nommo.

Aztec mythology

In Aztec mythology, Tonatiuh (Nahuatl: Ollin Tonatiuh, "Movement of the Sun") was the sun god. The Aztec people considered him the leader of Tollan (heaven). He was also known as the fifth sun, because the Aztecs believed that he was the sun that took over when the fourth sun was expelled from the sky. According to their cosmology, each sun was a god with its own cosmic era. According to the Aztecs, they were still in Tonatiuh's era. According to the Aztec creation myth, the god demanded human sacrifice as tribute and without it would refuse to move through the sky. It is said that 20,000 people were sacrificed each year to Tonatiuh and other gods, though this number is thought to be inflated either by the Aztecs, who wanted to inspire fear in their enemies, or the Spaniards, who wanted to vilify the Aztecs. The Aztecs were fascinated by the sun and carefully observed it, and had a solar calendar similar to that of the Maya. Many of today's remaining Aztec monuments have structures aligned with the sun.[2]

In the Aztec calendar, Tonatiuh is the lord of the thirteen days from 1 Death to 13 Flint. The preceding thirteen days are ruled over by Chalchiuhtlicue, and the following thirteen by Tlaloc.

Buddhism

In Buddhist cosmology, the bodhisattva of the Sun is known as Ri Gong Ri Guang Pu Sa (The Bright Solar Bodhisattva of the Solar Palace) / Ri Gong Ri Guang Tian Zi (The Bright Solar Prince of the Solar Palace) / Ri Gong Ri Guang Zun Tian Pu Sa (The Greatly Revered Bright Solar Prince of the Solar Palace / one of the 20 or 24 guardian devas). In Sanskrit, He is known as Suryaprabha. He is usually depicted with Yue Gong Yue Guang Pu Sa (The Bright Lunar Bodhisattva of the Lunar Palace) / Yue Gong Yue Guang Tian Zi ( The Bright Lunar Prince of the Lunar Palace) / Yue Gong Yue Guang Zun Tian Pu Sa (The Greatly Revered Bright Lunar Prince of the Lunar Palace / one of the 20 or 24 guardian devas known as Candraprabha in Sanskrit. With Yao Shi Fo / Bhaisajyaguru Buddha (Medicine Buddha), these two bodhisattvas create the Dong Fang San Sheng or the Three Holy Sages of the East.

Chinese mythology

In Chinese mythology (cosmology), there were originally ten suns in the sky, who were all brothers. They were supposed to emerge one at a time as commanded by the Jade Emperor. They were all very young and loved to fool around. Once they decided to all go into the sky to play, all at once. This made the world too hot for anything to grow. A hero named Hou Yi shot down nine of them with a bow and arrow to save the people of the earth. He is still honored this very day. In another myth, the solar eclipse was caused by the magical dog of heaven biting off a piece of the sun. The referenced event is said to have occurred around 2,160BCE. There was a tradition in China to make lots of loud celebratory sounds during a solar eclipse to scare the sacred "dog" away. The Deity of the Sun in Chinese mythology is Ri Gong Tai Yang Xing Jun (Tai Yang Gong / Grandfather Sun) or Star Lord of the Solar Palace, Lord of the Sun. In some mythologies, Tai Yang Xing Jun is believed to be Hou Yi. Tai Yang Xing Jun is usually depicted with the Star Lord of the Lunar Palace, Lord of the Moon, Yue Gong Tai Yin Xing Jun (Tai Yin Niang Niang / Lady Tai Yin).

Christianity

See also: Sol Invictus and Jesus Christ in comparative mythology

Ancient Egypt

Sun worship was prevalent in ancient Egyptian religion. The earliest deities associated with the sun are all goddesses: Wadjet, Sekhmet, Hathor, Nut, Bast, Bat, and Menhit. First Hathor, and then Isis, give birth to and nurse Horus and Ra. Hathor the horned-cow is one of the 12 daughters of Ra, gifted with joy and is a wet-nurse to Horus.

The Sun's movement across the sky represents a struggle between the Pharaoh's soul and an avatar of Osiris. Ra travels across the sky in his solar-boat; at dawn he drives away the demon Apep of darkness. The "solarisation" of several local gods (Hnum-Re, Min-Re, Amon-Re) reaches its peak in the period of the fifth dynasty.

Rituals to the god Amun who became identified with the sun god Ra were often carried out on the top of temple pylons. A Pylon mirrored the hieroglyph for 'horizon' or akhet, which was a depiction of two hills "between which the sun rose and set",[3] associated with recreation and rebirth. On the first Pylon of the temple of Isis at Philae, the pharaoh is shown slaying his enemies in the presence of Isis, Horus and Hathor. In the eighteenth dynasty, Akhenaten changed the polytheistic religion of Egypt to a monotheistic one, Atenism of the solar-disk and is the first recorded state monotheism. All other deities were replaced by the Aten, including Amun-Ra, the reigning sun god of Akhenaten's own region. Unlike other deities, the Aten did not have multiple forms. His only image was a disk—a symbol of the sun.

Soon after Akhenaten's death, worship of the traditional deities was reestablished by the religious leaders (Ay the High-Priest of Amen-Ra, mentor of Tutankhaten/Tutankhamen) who had adopted the Aten during the reign of Akhenaten.

Hinduism

The Ādityas are one of the principal deities of the Vedic classical Hinduism belonging to Solar class. In the Vedas, numerous hymns are dedicated to Mitra, Varuna, Savitr etc.

Even the Gayatri mantra, which is regarded as one of the most sacred of the Vedic hymns is dedicated to Savitr, one of the principal Ādityas. The Adityas are a group of solar deities, from the Brahmana period numbering twelve. The ritual of sandhyavandanam, performed by Hindus, is an elaborate set of hand gestures and body movements, designed to greet and revere the Sun.

The sun god in Hinduism is an ancient and revered deity. In later Hindu usage, all the Vedic Ādityas lost identity and metamorphosed into one composite deity, Surya, the Sun. The attributes of all other Ādityas merged into that of Surya and the names of all other Ādityas became synonymous with, or epithets of, Surya.

The Ramayana has Rama as a descendant of the Surya, thus belonging to the Suryavansha or the clan of the Sun. The Mahabharata describes one of its warrior heroes, Karna, as being the son of the Pandava mother Kunti and Surya.

The sun god is said to be married to the goddess Ranaadeh, also known as Sanjnya. She is depicted in dual form, being both sunlight and shadow, personified. The goddess is revered in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

The charioteer of Surya is Aruna, who is also personified as the redness that accompanies the sunlight in dawn and dusk. The sun god is driven by a seven-horsed Chariot depicting the seven days of the week.

In India, at Konark, in the state of Odisha, a temple is dedicated to Surya. The Konark Sun Temple has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Surya is the most prominent of the navagrahas or nine celestial objects of the Hindus. Navagrahas can be found in almost all Hindu temples. There are further temples dedicated to Surya, one in Arasavilli, Srikakulam District in AndhraPradesh, one in Gujarat at Modhera and another in Rajasthan. The temple at Arasavilli was constructed in such a way that on the day of Radhasaptami, the sun's rays directly fall on the feet of the Sri Suryanarayana Swami, the deity at the temple.

Chhath (Hindi: छठ, also called Dala Chhath) is an ancient Hindu festival dedicated to Surya, the chief solar deity, unique to Bihar, Jharkhand and the Terai. This major festival is also celebrated in the northeast region of India, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Chhattisgarh. Hymns to the sun can be found in the Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism. Practiced in different parts of India, the worship of the sun has been described in the Rigveda. There is another festival called Sambha-Dasami, which is celebrated in the state of Odisha for the surya.

The Gurjars (or Gujjars), were Sun-worshipers and are described as devoted to the feet of the sun god Surya. Their copper-plate grants bear an emblem of the Sun and on their seals too, this symbol is depicted.[4]

Indonesian mythology

Solar gods have a stronger presence in Indonesian mythology. In some cases the Sun is revered as a "father" or "founder" of the tribe. This may apply for the whole tribe or only for the royal and ruling families. This practise is more common in Australia and on the island of Timor, where the tribal leaders are seen as direct heirs to the sun god.

Some of the initiation rites include the second reincarnation of the rite's subject as a "son of the Sun", through a symbolic death and a rebirth in the form of a Sun. These rituals hint that the Sun may have an important role in the sphere of funerary beliefs. Watching the Sun's path has given birth to the idea in some societies that the deity of the Sun descends in to the underworld without dying and is capable of returning afterward. This is the reason for the Sun being associated with functions such as guide of the deceased tribe members to the underworld, as well as with revival of perished. The Sun is a mediator between the planes of the living and the dead.

Theosophy

Solar myth

Three theories exercised great influence on nineteenth and early twentieth century mythography, beside the Tree worship of Mannhardt and the Totemism of J. F. McLennan, the "Sun myth" of Alvin Boyd Kuhn and Max Müller.

R. F. Littledale criticized the Sun myth theory when he illustrated that Max Müller on his own principles was himself only a Solar myth, whilst Alfred Lyall delivered a still stronger attack on the same theory and its assumption that tribal gods and heroes, such as those of Homer, were mere reflections of the Sun myth by proving that the gods of certain Rajput clans were really warriors who founded the clans not many centuries ago, and were the ancestors of the present chieftains.[6]

Solar barge and sun chariot

A "solar barge" (also "solar bark", "solar barque", "solar boat" and "sun boat") is a mythological representation of the sun riding in a boat. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter-long vessel that was sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. This boat was rediscovered in May 1954 when archeologist Kamal el-Mallakh and inspector Zaki Nur found two ditches sealed off by about 40 blocks weighing 17 to 20 tonnes each. This boat was disassembled into 1,224 pieces and took over 10 years to reassemble. A nearby museum was built to house this boat.[7]

Other sun boats were found in Egypt dating to different pharonic dynasties.[8]

Examples include:

- Neolithic petroglyphs which (it has been speculated) show solar barges

- The many early Egyptian goddesses who are related as sun deities and the later gods Ra and Horus depicted as riding in a solar barge. In Egyptian myths of the afterlife, Ra rides in an underground channel from west to east every night so that he can rise in the east the next morning.

- The Nebra sky disk, which is thought to show a depiction of a solar barge.

- Nordic Bronze Age petroglyphs, including those found in Tanumshede often contains barges and sun crosses in different constellations.

Examples include:

- In Norse mythology, the chariot of the goddess Sól, drawn by Arvak and Alsvid. The Trundholm sun chariot dates to the Nordic Bronze Age, more than 2,500 years earlier than the Norse myth, but is often associated with it.

- Greek Helios riding in a chariot,[9] (see also Phaëton)[10]

- Sol Invictus depicted riding a quadriga on the reverse of a Roman coin.[11]

- Vedic Surya riding in a chariot drawn by seven horses

Male and female

Among modern English speakers, solar deities are popularly thought of as male counterparts of the lunar deity (usually female); however, sun goddesses are found on every continent (e.g. Amaterasu in Japanese belief) paired with male lunar deities. Among the earliest records of human beliefs, the early goddesses of the Egyptian pantheon carried a sun above their head as a symbol of dignity (as daughters of Ra). The sun was a major aspect of Egyptian symbols and hieroglyphs, all the lunar deities of that pantheon were male deities. The cobra (of Pharaoh Son of Ra), the lioness (daughter of Ra), the cow (daughter of Ra), the dominant symbols of the most ancient Egyptian deities, carried their relationship to the sun atop their heads; they were female and their cults remained active throughout the history of the culture. Later a sun god (Aten) was established in the eighteenth dynasty on top of the other solar deities, before the "aberration" was stamped out and the old pantheon re-established. When male deities became associated with the sun in that culture, they began as the offspring of a mother (except Ra, King of the Gods who gave birth to himself).

Some mythologists, such as Brian Branston, Patricia Monaghan and Janet McCrickard, contend that sun goddesses are as common as, or even more common, worldwide than their male counterparts. They also claim that the belief that solar deities are primarily male is linked to the fact that a few better known mythologies (such as those of late classical Greece and late Roman mythology) rarely break from this rule, although closer examination of the earlier myths of those cultures reveal a very different distribution than the contemporary popular belief. The dualism of sun/male/light and moon/female/darkness is found in many (but not all) late southern traditions in Europe that derive from Orphic and Gnostic philosophies.

In Germanic mythology the Sun is female and the Moon is male. The corresponding Old English name is Siȝel [ˈsɪjel], continuing Proto-Germanic *Sôwilô or *Saewelô. The Old High German Sun goddess is Sunna. In the Norse traditions, every day, Sól rode through the sky on her chariot, pulled by two horses named Arvak and Alsvid. Sól also was called Sunna and Frau Sunne, from which are derived the words: Sun and Sunday.

Other cultures that have sun goddesses include: The Lithuanians and Latvians (Saule), the Finns (Päivätär, Beiwe) and the related Hungarians (Xatel-Ekwa) and the Slavic peoples (Solntse). Sun goddesses are found around the world; in Arabia (Al-Lat), Australia (Bila, Walo), India (Bisal-Mariamna, Bomong, Kn Sgni) and Sri Lanka (Pattini); among the Hittites (Wurusemu), Egyptians (Sekhmet) and Babylonians (Shapash); in Native America, among the Cherokee (Unelanuhi), Natchez (Wal Sil), Inuit (Malina) and Miwok (Hekoolas).

Missing sun

The missing sun is a theme in the myths of many cultures,[citation needed] sometimes including the themes of imprisonment, exile, or death. The missing sun is often used to explain various natural phenomena, including the disappearance of the sun at night, shorter days during the winter, and solar eclipses.

Some other tales are similar, such as the Sumerian story of the goddess Inanna's descent into the underworld. These may have parallel themes, but do not fit in this motif unless they concern a solar deity.

In late Egyptian mythology, Ra passes through Duat (the underworld) every night. Apep has to be defeated in the darkness hours for Ra and his solar barge to emerge in the east each morning.

In Japanese mythology, the sun goddess Amaterasu is startled by the behavior of her brother Susanoo and hides in a cave, plunging the world into darkness until she is willing to emerge. It has been suggested that the story is allegorical, symbolising that the sun goddess hiding in a cave is a metaphor for the sun exhibiting quiet periods such as the Maunder Minimum. This allegory has been used in literature such as Masks of the Lost Kings.[12]

In Norse mythology, the gods Odin and Tyr both have attributes of a sky father, and they are doomed to be devoured by wolves (Fenrir and Garm, respectively) at Ragnarok. Sól, the Norse sun goddess, will be devoured by the wolf Skoll.

In Hindu astronomy, Rahu and Ketu ate the sun or moon to cause lunars and solar eclipses. In later, more scientific years, their names were given to the Lunar nodes.

See also

- Abram Smythe Palmer

- Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto

- Beaivi

- Belenos

- Black Sun (deity)

- Black Sun (disambiguation)

- Canticle of the Sun

- Fire worship

- Five Suns

- Giza Solar boat museum

- Guaraci

- Golden hat

- Heliocentrism

- July Morning

- Konark Sun Temple

- List of solar deities

- Lunar deity

- Nature worship

- Order of the Solar Temple

- Phoenix

- Solar calendar

- Solar symbol

- Stonehenge

- Thelema

- White horse (mythology)

- Winged sun

References

- ^ "Sun worship." Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009

- ^ Biblioteca Porrúa. Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Historia y Etnología, ed. (1905). Diccionario de Mitología Nahua (in Spanish). México. pp. 648, 649, 650. ISBN 978-9684327955.

- ^ Wilkinson, op. cit., p.195

- ^ Lālatā Prasāda Pāṇḍeya (1971). Sun-worship in ancient India. Motilal Banarasidass. p. 245.

- ^ Powell, A.E. The Solar System London:1930 The Theosophical Publishing House (A Complete Outline of the Theosophical Scheme of Evolution). Lucifer, represented by the sun, the light.

- ^ William Ridgeway (Cambridge: 1915). "Solar Myths, Tree Spirits, and Totems, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of Non-European Races". Cambridge University Press. TheatreHistory.com. pp. 11–19. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Siliotti, Alberto, Zahi Hawass, 1997 "Guide to the Pyramids of Egypt" p. 54-55

- ^ "Egypt solar boats".

- ^ "Helios". Theoi.com. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ "Helios & Phaethon". Thanasis.com. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Probus Coin

- ^ http://www.tombane.com

Bibliography

- Azize, Joseph (2005) The Phoenician Solar Theology. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-210-6.

- Olcott, William Tyler (1914/2003) Sun Lore of All Ages: A Collection of Myths and Legends Concerning the Sun and Its Worship Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-96027-7.

- Hawkins, Jacqueta Man and the Sun Gaithersburg, MD, USA:1962 SolPub Co.

- McCrickard, Janet. "Eclipse of the Sun: An Investigation into Sun and Moon Myths." Gothic Image Publications. ISBN 0-906362-13-X.

- Monaghan, Patricia. "O Mother Sun: A New View of the Cosmic Feminine." Crossing Press, 1994. ISBN 0-89594-722-6

- Ranjan Kumar Singh. Surya: The God and His Abode. Parijat. ISBN 81-903561-7-8

External links

- The Worship of the Sun Among the Aryan Peoples of Antiquity by Sir James G. Frazer (from archive.org)

- The Sun God Ra and Ancient Egypt

- The Sun God and the Wind Deity at Kizil by Tianshu Zhu, in Transoxiana Eran ud Aneran, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- Comparison between the Egyptian Hymn of Aten and modern scientific conceptions

|

| The warrior goddess Sekhmet, shown with her sun disk and cobra crown |

.jpg)

.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

+001.jpg)

.jpg)